A portmanteau of ‘SMS’ and ‘phishing’, this rather clunky term describes a cyber-telecoms scam many of us have encountered

Ask 100 random strangers if they know what ‘smishing’ is, and few would know what you’re talking about.

However, once the term is explained, many would realize they have direct experience of this social engineering phenomenon.

What is smishing?

Smishing is a form of phishing in which cybercriminals send SMS messages from purportedly trusted sources to dupe victims into clicking a malicious link or giving them personal data.

Posing as banks, government agencies, or even friends or family, fraudsters deploy social engineering techniques to trick victims into handing over bank details, login credentials, Social Security numbers, and other sensitive information.

Those who fall prey to smishing – or ‘SMS phishing’ – attacks can have their identities stolen, bank accounts emptied, or end up with malware installed on their phone.

How popular are smishing attacks?

Banks and anti-fraud agencies around the world warn that fraudulent text messages are becoming more numerous and sophisticated.

The number of smishing attacks reported to infosec firm Proofpoint’s spam text service soared by nearly 700% in the first six months of 2021.

Fueled by the online shopping boom during the Covid-19 pandemic, parcel delivery-related SMS were three times as common as banking scams.

UK consumer magazine Which?, meanwhile, said it received more than 9,000 reports of scams via text or phone between March and September 2021.

The Verizon Mobile Security Index 2020 has hinted at a growing problem, reporting that 85% of attacks on mobile devices are not directed via email.

There has invariably been a spike in social engineering scams during serious emergencies such as natural disasters and, as in 2020, pandemics.

These are designed to exploit the public’s fears and anxieties, making their victims an easier target.

In February 2020, for instance, the South Korean government issued an alert about fraudulent messages offering free masks, and in March came warnings in the US of fraudulent shipping alerts directing victims to update delivery preferences and provide credit card details.

Why is smishing a popular attack method?

Most adults – and a growing number of children – carry a smartphone at all times. Research shows that the average SMS open rate is 98%, compared to just 20% for emails.

Cybercrooks can readily automate the sending of SMS messages to thousands or even millions of phone number combinations.

In contrast to emails, there is apparently no viable way for users to block or flag suspicious SMS messages.

It’s also neither possible to reverse numbers to determine if the proclaimed sender is “legitimate”, nor receive alerts if incoming SMS are suspected scams, Larry Trowell, principal security consultant at design automation company Synopsys, told The Daily Swig.

Smishing uses social engineering to dupe victims into handing over credentials

Smishing uses social engineering to dupe victims into handing over credentials

How does smishing work?

In a typical smishing scam, victims are instructed to perform a variety of self-damaging actions in the misguided belief they are getting something useful (like activating a credit card), exciting (a prize or exclusive offer), or protecting themselves from some immediate threat (such as a warning they have been infected with malware).

These actions can include:

- Replying to the SMS with specific personal information

- Clicking a link that downloads malware or directs them to a credible-looking website in order to disclose personal details

- Call a premium rate ‘customer services’ number

- Wire money into the criminal’s bank accounts

Cybercrooks impersonate a wide range of organizations, such as banks, healthcare agencies, or courier firms.

Attackers often inject a sense of urgency (“Offer expires today!” or “Act now or your account will be suspended!”) to frighten the target into following instructions that might have raised suspicions, had they taken more time to think.

Spear-phishing, which customizes messages to a specific individual or organization, makes such gambits more credible.

RELATED Google partners with US victim support network to fight Covid-19 scams

Multi-pronged attacks – SMS combined with a phone call and/or authentic-looking website – also makes nefarious schemes more believable.

“They may use an SMS message to prime the victim by telling them to look out for an email,” Javvad Malik, security awareness advocate at KnowBe4, a provider of security awareness training, told The Daily Swig.

“By going through different channels simultaneously, people are often led to believe that only a legitimate organisation would have all their details.”

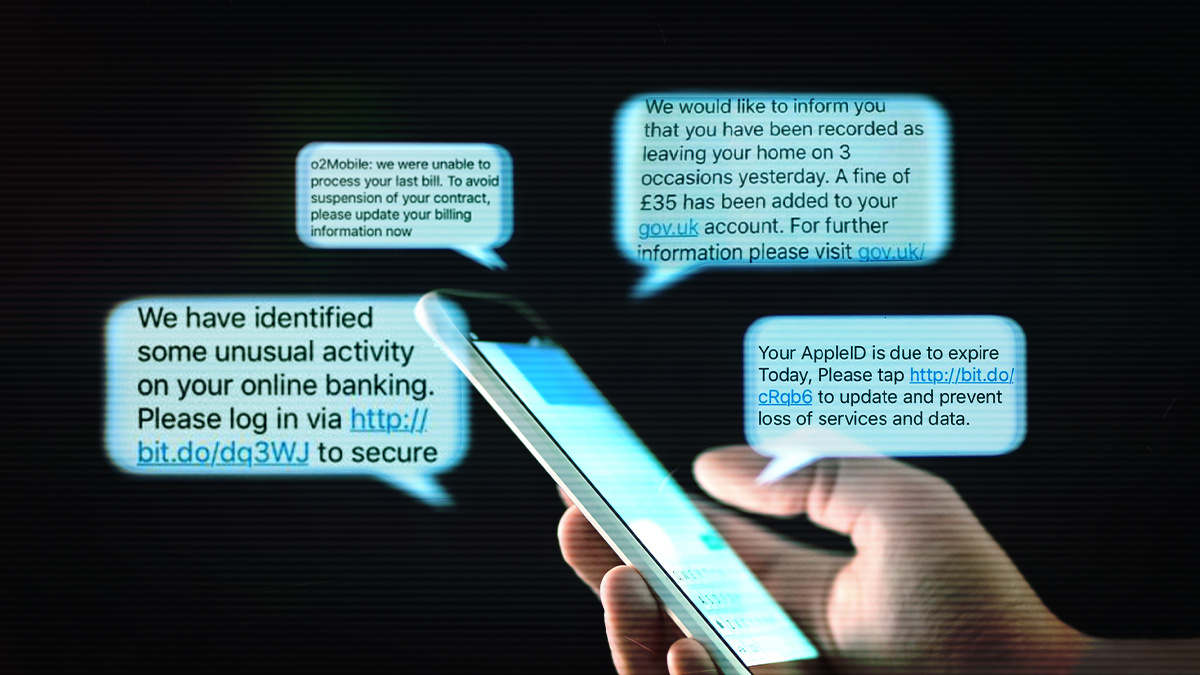

Examples of smishing

Some smishing messages are easy to spot since messages are characterized by misspellings, bad grammar, and implausible calls to action.

However, many are highly convincing and the red flags – there are nearly always red flags, however subtle – are tricky to detect.

Three particularly sophisticated schemes reported in recent years include:

- Messages during the Covid-19 pandemic urging the recipient to self-isolate because they supposedly in close contact with the sender, who claimed to have tested positive for the virus

- In 2018, 125 customers of the Ohio-based Fifth Third Bank entered their account credentials into a spoofed website to unlock their account – instead, cybercrooks hijacked their accounts and withdrew $68,000 from 17 ‘cardless’ ATMs

- A UK customer of Santander bank was defrauded of £22,700 in 2016 after revealing his ‘one-time password’ to a spoofed bank phone number that materialized in an earlier, genuine thread with Santander

What is the difference between smishing and vishing?

Vishing attacks are designed to dupe victims via voice calls.

Attackers often use Voice over IP (VoIP) services such as Skype since they can readily spoof caller IDs of trusted organizations. Robocalls are often used, while the emergence of deep fake audio increases the risk of victims being defrauded by the manipulated voices of people they know and trust.

Psychology of a smishing victim

“Everyone is vulnerable to both malicious emails and malicious SMS,” Georgia Crossland, who co-authored an academic paper on the behavioural dimension of cybersecurity that was submitted to the UK government, told The Daily Swig.

“Research shows even experts can be caught out,” added the London-based PhD student, “either because the attack was particularly convincing, or because of environmental reasons, such work stress, or a security-productivity trade-off.”

INSIGHT SIM swap fraud – an explainer

Cognitive biases “influence our vulnerabilities”, she said. She cites the optimism bias, where individuals believe themselves less susceptible than others and are therefore “less likely to take preventative methods”.

Persuasion techniques popularized by Dr Robert Cialdini in the 1980s can often be identified in phishing attacks, Crossland says – ‘scarcity’, for instance (“click before it’s too late”), or ‘liking’ (we tend to trust people or organizations we like).

“For example, I received the Whole Foods voucher scam message on WhatsApp from three separate ‘friends’ and very nearly clicked on the link,” admits Crossland.

How to stop smishing text messages snaring you

While smishing can’t exactly be defeated, there are actions you can take to ensure you don’t fall for them.

Security experts generally preach a safety-first mindset when deciding whether to respond to SMS messages.

“If you don’t know with certainty who sent you the message, don’t click any links,” says Larry Trowell of Synopsys. “This is also true of seemingly branded messages. If you didn’t sign up to be notified with package delivery notifications, for instance, don’t click the link.

“If it seems unusual that a company is sending you text messages to download their latest app or to get a discount code, then trust your instincts.”

This checklist encapsulates expert advice on spotting and dealing with suspicious SMS:

- Don’t click on a link or call a number within an unsolicited SMS, or submit personal information in response

- Verify a message’s authenticity by finding the purported sender’s website and official contact details online

- If it looks too good to be true, it probably is

- Delete all suspicious texts

- Block SMS from unknown numbers – you can do this on iPhones and Android phones

- ‘5000’ numbers indicate that the message was sent via email and is likely to be malicious

- Texting ‘STOP’ to prevent future messages might only confirm your number is in use and invite further messages

It can sometimes be difficult to spot a smishing attempt, but there are often red flags

It can sometimes be difficult to spot a smishing attempt, but there are often red flags

Security awareness training

“There usually isn’t the equivalent of an email gateway for SMS messages,” says Javvad Malik of KnowBe4. “So organizations are almost completely reliant on their staff being able to spot, and not fall victim to, a smishing attack.”

Effective training and clear security policies are therefore paramount.

But Georgia Crossland, who was part of the winning team at The Atlantic Council’s inaugural UK Cyber 9/12 Student Challenge, warns that fear-based awareness campaigns “often scare people into believing there is nothing they can do to reduce threats personally, leading people not to try.

“We need to do more qualitative research to better understand the human factor in information security,” she adds.

However, technological solutions can still be part of the solution. For instance, the SMS SenderID Protection Registry, a UK trial, blocked more than 400 scam variants as of April 2020 by allowing organizations to register and protect their message headers.

How to report smishing

If you receive a suspicious SMS that appears to impersonate an organization, you can alert them directly.

Alternatively, you can forward it to an anti-fraud SMS service if one exists in your country (7726 in the US and UK for instance), or Google ‘report smishing’ to find the relevant authority in your country (Scamwatch in Australia, for example).

If you’ve responded to what you suspect might be a fraudulent SMS, you should also alert your bank and phone provider, which can set up security alerts.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE Tor security: Peeling back the layers of the onion