Automation and federalized structure are strategic priorities for MITRE Corporation as attack surface mushrooms

UPDATED It all began on October 30, 1999 with a batch of 321 entries.

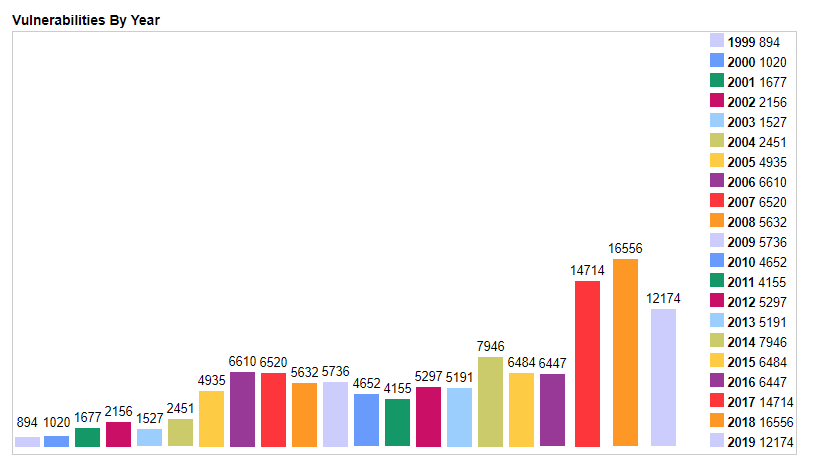

Twenty years later – to the day (October 30, 2019) – and the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database has grown to include 124,000 registered security vulnerabilities.

A repository of common identifiers for publicly known vulnerabilities, the CVE registry has provided a common vocabulary for identifying and mitigating cyber weaknesses since before the millennium.

When it launched in 1999, users were still frustrated by glacially slow dial-up speeds, and the infosec community was hamstrung by taxonomical confusion.

De facto standard

Speaking to The Daily Swig last year, Chris Levendis, CVE project lead for MITRE Corporation, which maintains the CVE project, recalled how multiple competing vulnerability databases meant that everyone used “their own vocabulary”.

Soon becoming the de facto standard, the CVE registry gave vendors, researchers, and end users a common nomenclature.

The rate at which common identifiers have been registered since attests to the dizzying – and accelerating – proliferation of vulnerabilities confronting the infosec community.

About three new vulnerabilities were added daily to the CVE database in 2000, its first full year of existence. By 2005 this number had risen to about 14, and MITRE says it now registers about 40 new entries a day.

Scaling the program through CNAs

Propelled, in part, by the burgeoning mobile, cloud, and IoT markets, the breakneck growth in the global attack surface has prompted MITRE to increase the number of CVE Numbering Authorities (CNAs), which are authorized to assign CVE numbers to vulnerabilities within their scope.

RELATED FIRST for security: Non-profit looks ahead to another 15 years of CVSS ratings

The number of CNAs, which include software vendors, open source projects, bug bounty platforms, and research groups, jumped from 87 in May 2018 to the present 104 organizations spanning 18 countries.

As well as onboarding “20 (projected) CNAs”, Levendis says the program’s 20th year has seen “the ongoing development of infrastructure services to support governance and operations in a federated environment, and the ongoing engagement of the CVE board and the CNAs to chart and execute the direction of the program”.

This “federated strategy”, devised to “scale the program” and “deliver the value of CVE to a much broader group of stakeholders”, appears to already be achieving the goals described by Levendis: to broaden CVE program adoption and coverage and, thus, “produce more CVEs, faster”.

Vulnerability trends

The number of vulnerabilities registered to the CVE database annually fluctuated within a narrow range between 2005 and 2016 – before jumping 128% from 6,447 in 2016 to 14,714 in 2017.

That number climbed again to 16,556 in 2018 and 2019 is on course to reach a similar number.

Automation is seen as key to continuing this upward trajectory, with CVE board member Karl Landfield telling The Daily Swig last year that working groups allow board members, CNAs, and the public to help drive further automation.

Asked about the most compelling vulnerability trends, Levendis cited the CWE 25 most dangerous software errors for 2019.

Topping this list of Common Weakness Enumerations (CWE) by an overwhelming margin was ‘Improper Restriction of Operations within the Bounds of a Memory Buffer’ (CWE-119).

“This CWE is a more general class that includes other CWEs as children such as the standard buffer overflow, out-of-bounds writes, and out-of-bounds reads,” said Levendis.

“Cross-site scripting flaws are also common,” he said, noting that XSS bugs attracted the second biggest number of CVEs globally.

“Although weakness types are not vulnerabilities per se,” he said, “the updated Top 25 list used a data-driven approach that leverages published CVE master list, related CWE mappings found within the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) National Vulnerability Database (NVD), as well as the Common Vulnerability Scoring System (CVSS) scores associated with each of the CVEs.”

The numbers behind the name

CVE IDs are routinely cited in security advisories and sometimes in media coverage of cybersecurity vulnerabilities.

Some of the most famous (or notorious) CVE entries include ‘Heartbleed’ (CVE-2014-0160), Shellshock (CVE-2014-6271, CVE-2014-7169, CVE-2014-7186, CVE-2014-7187, CVE-2014-6277, CVE-2014-6278) and BlueKeep (CVE-2019-0708).

A security researcher who uncovers a new vulnerability must contact the relevant CNA to coordinate assignment of a CVE ID.

Should the vulnerability remain outside any CNA’s current remit, they can instead contact the non-CNA vendor. The researcher or non-vendor CNA can submit an ID request to MITRE, which then assigns a CVE ID.

“Coordinating with the vendor or project is what’s most important, because the vendors and projects know the most about their products, and are in best position to validate and confirm the vulnerability,” said Levendis.

This article was updated on Monday, November 4 after further updates from MITRE Corporation.

READ MORE CVE board looks ahead to the next 20 years of vulnerability identification