Personal data leaked through mix-blend-mode feature

A vulnerability in CSS allows attackers to steal personal information through web browsers by exploiting a visual feature.

Users visiting a specially crafted website could unintentionally deanonymize themselves if a property in CSS3 is abused by attackers.

The side-channel attack, which is exploited through the CSS3 mix-blend-mode feature, can only be exploited if a website allows itself to be framed via an iframe element – a tool that effectively embeds a webpage within a webpage.

If a site creator wanted to place a third-party advertisement onto their page, for instance, or have a social media button, an iframe would allow them to do that while keeping the visitor on their site.

While the creator may be linking to a different domain, using these types of iframes does not grant them access to content from the third-party site – such as a user’s Facebook details, if they had embedded a Facebook button.

“By chance I stumbled on Pinterest’s homepage which was displaying my Facebook name and picture inside an iframed Facebook button,” Ruslan Hablov, a security researcher, wrote recently on his blog Evonide.

“You would expect that a site like Pinterest can’t just read content from the iframe as the same-origin policy would disallow accessing any cross-origin iframe content by default so this should be fine, right?”

Not with the CSS3 exploit.

Hablov is one of the researchers that discovered the side-channel attack, which has chiefly appeared on Chrome and Firefox browsers, and can determine the content of a cross-origin iframe by manipulating the visual effects enabled with the mix-blend-mode CSS3 feature.

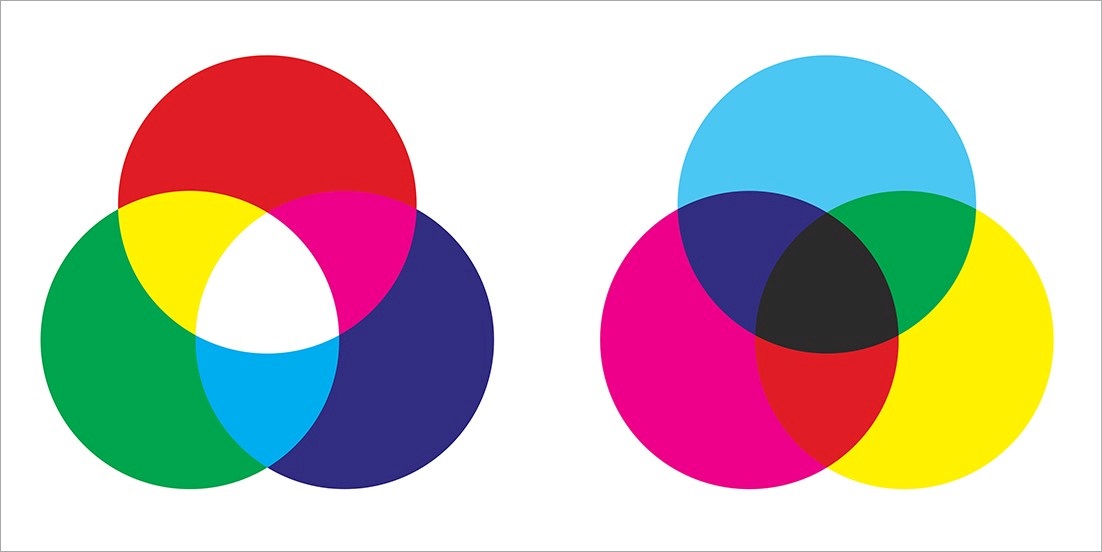

First introduced in 2016, mix-blend-mode is a property that decides how web content, such as an image or text, blends with its background through the interaction of stacked layers – a sort of filter that creates effects like saturation, transparency, or lightening.

An attacker can abuse this property on a cross-origin iframe by stacking multiple layers in order to create a reaction between the blending elements, slowly revealing the color of the text or data found within the iframe.

Many different filters can be used to achieve this, some better than others, and dependent on the color of the original data.

“Mixing together different blend modes allows you to come up with a computationally powerful framework,” explained Hablov.

“Let’s say we have a target pixel with the reddish color rgb(160, 0, 0). Our goal is to leak the highest bit of its red channel. The binary representation would be rgb(10100000b, 0, 0) so we would like to detect that the highest bit is a 1. To leak this specific bit we have to adjust the colors of the first three preprocess layers: difference, lighten and difference.”

Using Facebook data as an example, Hablov said the side-channel attack could easily reveal a user’s name, profile picture, and like status - provided that a person was already logged on to the social media site.

A profile picture would be leaked in about five minutes.

“Ways to improve performance would have required to implement testing for whole characters instead of leaking individual pixels,” said Hablov.

“Additionally, leaking only a low-resolution black and white version of the profile picture would also improve performance significantly. However, our leaking speed would have been capped at about 1 bit / 16ms (60Hz) due to the JavaScript performance API anyways.”

Issues with the mix-blend-mode feature were first reported in 2017 and assigned as CVE-2017-15417 through the Chromium bug tracker.

According to Hablov, the new discovery of this vulnerability has been disclosed responsibly, and browsers like Internet Explorer, Microsoft Edge, and Safari do not appear to be affected.

The bug has been fully patched in Firefox 60 and users are recommended to update their browsers to the latest versions.