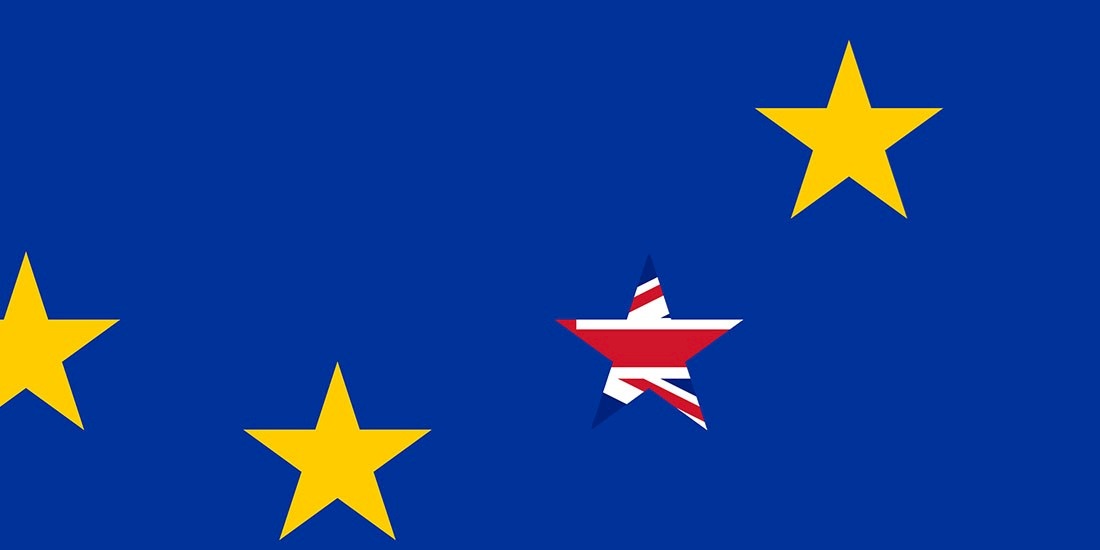

What will data-sharing look like post-Brexit?

Security was one of the topics of choice at the House of Lords yesterday, as the committee of Home Affairs sought to understand how data-sharing between the UK and EU will work after Brexit.

Britain is expected to leave the 28-member state bloc in March next year, opening the door to a new security treaty.

Both Richard Martin, a National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC) lead, and Steve Smart director of intelligence at the National Crime Agency (NCA), were present to speak on the proposed UK-EU strategy.

“From a policing point of view, we would want to be able to continue to operate as we do, with all the tools that we have at our disposals now, from EU arrest warrants, through to our interaction in Europol,” said Martin.

“This is with a future focus as well,” he added. “So [as to have] the ability to grow with the EU to respond to future threats.”

UK crime fighting agencies like the NCA and the Metropolitan Police currently share crime databases with Europol, the law enforcement agency of the European Union that focuses on combatting organized crime and terrorism.

The Schengen Information System (SIS II), which is a database maintained by the European Commission, is one of the tools that British law enforcement fears it will lose access to.

“At the moment when a police officer checks a person on the street, both the national criminal database and the SIS automatically gets checked,” said Martin.

“It’s really essential that while that person is in front of you, or that vehicle, or that property, we have the ability to do that so the officer doesn’t have to double think, or check two databases.

“There’s no double checking.”

According to Martin, SIS II was used by British forces 539 million times last year, which helped lead to crucial arrests and even to register sex offenders.

Losing this system would likely mean a switch to Interpol’s database I-24/7 – an information exchange significantly more limited due to its lack of automation.

The data flow works both ways too, with the UK having circulated 1.2 million criminal alerts to its European counterparts in 2017 alone.

“That’s a dataset [SIS II] that our EU partners are feeding, and are also seeing information that we’re putting on,” said Smart.

“It allows us to be back in touch with them and build a picture. If we haven’t got that data coming in, it’s a real problem.”

The European Arrest Warrant, the European Criminal Records Information System (Ecris), and Europol itself are other aspects of the current UK-EU relation that both Martin and Smart were keen to hold onto in a post-Brexit world.

Britain’s more advanced technical expertise, however, which Martin said often helped steer Europol’s strategic arm, should put the nation in a prime position to maintain its influence and data-sharing capabilities with the EU.

Its role within the Five Eyes signals intelligence sharing partnership – an alliance between the US, UK, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand – also provides the UK with a strong hand, as an exit from SIS II would negatively impact the NSA and its partner agencies.

The EU has also been working on improving its cybersecurity and information-sharing cooperation with NATO, within which the UK contributes the third highest amount in defense spending.

But some aren’t so convinced.

At the Munich Security Conference in February, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker warned that a common crime and defense strategy should not be used as a bargaining chip on other issues at the Brexit negotiating table.

British Prime Minister Theresa May has remained steadfast in that a new security treaty would provide legal basis for continued cooperation between the UK and EU – the failure in doing so significantly weakening nations’ shared goals of countering crime and terror.

“From a security perspective, we need to come up with a treaty that is win-win for both sides,” said Smart.

“Obviously there are difficulties because this isn’t just a security treaty but that’s an issue for government at the negotiating tables.”

Before the European Arrest Warrant, Britain was extraditing 60 people a year, Smart said. Since its implementation in 2004 the UK has extradited over 10,000 people to Europe.

The Home Affairs committee continues its inquiry into the proposed UK-EU security treaty, which is expected to come into effect in 2021.