2,500 like-minded people descend on South West England to ‘hack the planet’

For three days at the end of August, the idyllic countryside of the West Midlands, known for its grassy knolls and quaint villages, was overrun by the curiosity driven and technologically inclined: hackers.

Taking place over three main stages this past weekend, the fourth annual Electromagnetic Field (EMF) festival saw 2,500 people congregating in and out of at least 120 talks, all focused around what it means to be a hacker today – an image miles away from the black hooded delinquent hunched behind a computer.

“I liked the fact that we weren’t all in a stuffy conference center,” said Tim Wilkes, an information security manager who attended EMF for the first time this year.

“It has a nice relaxed atmosphere and wasn’t just InfoSec based,” he told The Daily Swig, perhaps putting EMF in an entirely different category than the sometimes-intense moods of big-ticket symposiums like Black Hat or DEF CON, both now primarily reserved for the global security elite.

“In today’s world, we sit in echo chambers of our own making,” said Wilkes. “Sometimes we need different perspectives on how to look at challenges. Being able to learn new skills, which aren’t necessarily relevant, is also fun.”

Wilkes added: “I can’t think how I’d use blacksmithing in my day-to-day job, but having a go still appeals!”

Since its inception in 2012, EMF has slowly grown into what may be best described as the Glastonbury of hacking festivals – a community-driven, volunteer-run event that brings together a diverse group of individuals under the umbrella of art, science, and engineering. Kids are welcome too.

Unlike the Vegas conferences, which spotlight cutting-edge attack methods and top industry lines, EMF sets itself apart by championing the DIY culture of breaking things and putting them back together, whether with physical or digital tools, and with a low budget that boasts how much you can really do with limited resources.

“This event almost didn’t happen – several times,” said Jonty Waering, one of the EMF founders, in his opening speech that kick-started the long weekend of robots and 3D printers, all set to a backdrop of a 19th century estate.

“This is the venue we have always wanted to run this event,” said Waering, having managed to successfully pull off the festival with a core group of 40 volunteers.

“We wanted to come back here but couldn’t because we couldn’t get an internet connection. It’s been remarkable that we managed to do it – we have dedicated fibre laid to the site this year.”

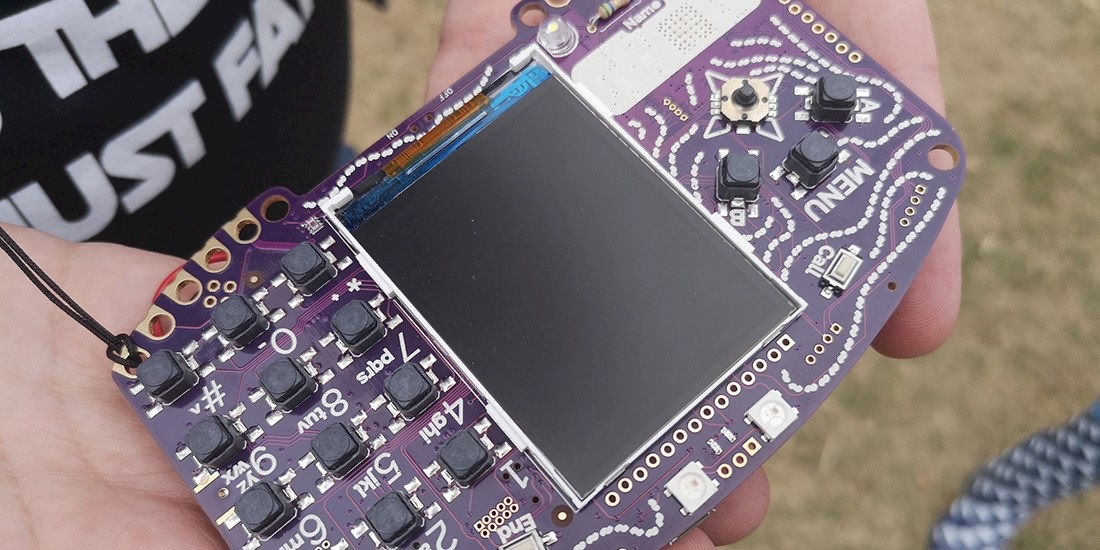

On top of creating its own power infrastructure, EMF also provided attendees with programmable badges – 2,5000 devices running open source phoneware that wearers could build mobile apps on.

“We have our own phone network,” Waering said. “The badges connect to it, they all have SIM cards, after this event the SIM cards will work anywhere in the world, just for data, but that’s still cool.”

He added: “They can do DMTF (Distributed Management Task Force) recognition so you can dial into them and make robots do things.”

With 100 watts of lasers on site, flamethrowers to play with, and satellites taking multispectral imaging from overhead each morning, it’s hard to imagine how anyone found time to listen in to the impressive manifold of lectures and workshops.

But those that did enjoyed content ranging from how to use Tor and what makes a good penetration tester, to all you need to know in order to make electronic instruments and work with spider silk.

Waering said: “While hacker and maker festivals are often computer and security focused, we aim for diversity so that people are exposed to new ideas and topics alongside the ones they’re expecting to see.”