‘All mobile internet networks are completely cut off,’ one journalist on the ground tells The Daily Swig

Sudan is suffering a country-wide internet shutdown that’s lasted more than a week so far, following a military coup.

On October 25, the military arrested the civilian prime minister, Abdalla Hamdok, and dissolved the democratic government set up after the fall of former president Omar al-Bashir.

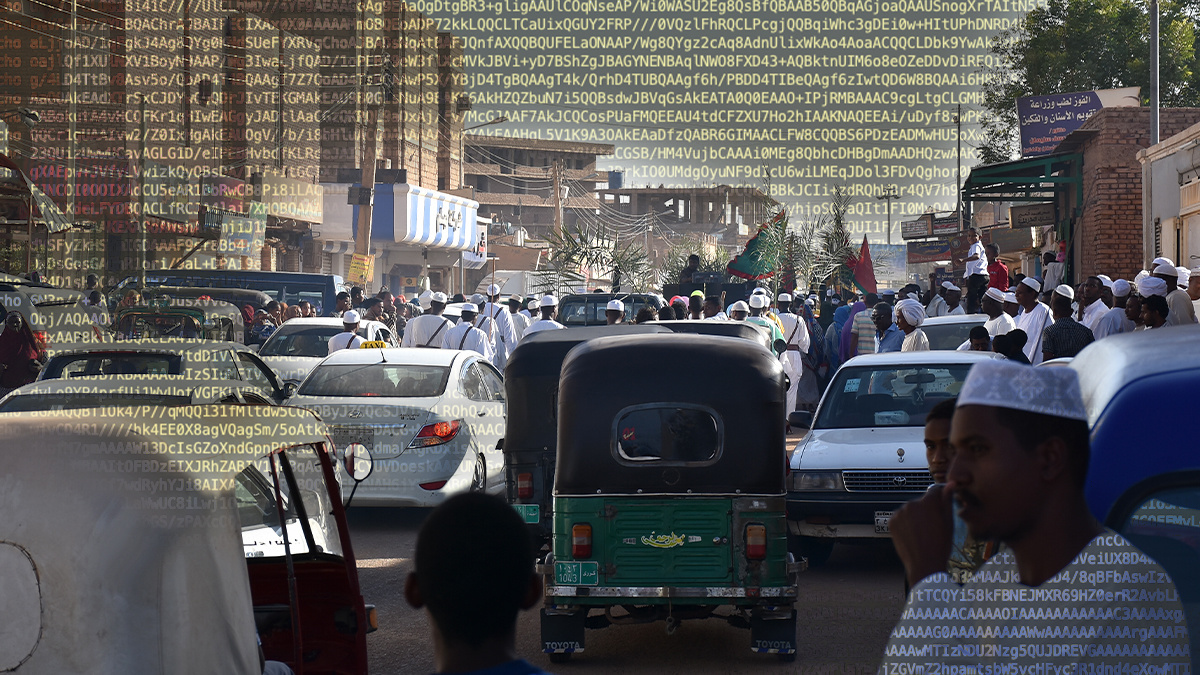

Hundreds of thousands of people turned out to protest. Troops are reported to have opened fire, killing at least 11 and injuring hundreds more.

Meanwhile, around 4pm local time that day, internet traffic dropped to almost zero and has stayed that way since, apart from a return of mobile service for about an hour, 35 hours after the initial disruption.

“All mobile internet networks are completely cut off; some fixed-line networks are operating on a small scale to serve government departments,” Sudanese journalist and human rights activist Hassan Ahmed Berkia tells The Daily Swig.

“The military forces are giving orders to employees of mobile phone companies under threat.”

Digital blockade

Web security and performance monitoring firm Cloudflare says the drop in traffic was sudden and unusual, and that it has affected all the major internet service providers (ISPs) in Sudan.

“Shutting down the internet is not as hard as people might imagine,” Cloudflare’s director of engineering, Celso Martinho, tells The Daily Swig.

“The government can order the local ISPs to stop peering traffic to other entities outside the country. If the ISPs comply, all they need to do is to stop announcing their routes to the outside internet; turning the internet off is a simple configuration change.”

RECOMMENDED Mauritian government’s plan to intercept web traffic marks ‘death knell for freedom of speech’

Meanwhile, security research firm Comparitech says it has noted a sharp increase in searches for virtual private networks (VPNs) within the country since the initial shutdown.

“During a shutdown, even software and services designed to bypass censorship, such as VPNs and other proxies, will be ineffective,” says Paul Bischoff, privacy advocate at Comparitech.

“However, as the internet starts to come back online, residents of Sudan should be prepared for online censorship.

Bischoff added: “Protestors can also consider using mesh networking apps to organise and communicate. Mesh networking apps typically use Bluetooth to connect devices over short distances so they can communicate even without access to the internet. For example, Bridgefy was recently used by protestors in Hong Kong.”

Sudan: A history of internet blackouts

Sudan has a long history of internet shutdowns. In December 2018, following protests calling for al-Bashir to step down, access was cut off for 68 days. Another mobile internet shutdown in the summer of 2019 lasted for 36 days.

Elsewhere in Africa, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Zimbabwe, Togo, Burundi, Chad, Mali, Nigeria, and Guinea all also restricted access to the internet or social media applications at some point during 2020.

“Shutting down the internet while a military coup is unveiling and protesters are out on the street is a clear sign that someone is trying to cover up something,” says Felicia Anthonio, campaigner and #KeepItOn lead at campaign group Access Now.

Read more of the latest cybersecurity news from Africa

“After authorities met protests for democracy in 2019 with a complete internet shutdown, the world was shocked by the atrocities that were perpetrated against the Sudanese people, and a return to this tactic is a major warning sign of what could follow.”

International pressure on Sudan is increasing, with the UAE, the US, Saudi Arabia, and the UK calling for an immediate restoration of the civilian government. Meanwhile, the World Bank has suspended its economic support to Sudan and says it won't process any new operations.

And, says Berkia, “the demonstrations are continuing, and I don’t think they will stop except in two cases – killing all the Sudanese people or reversing the military coup.”

RELATED Africa sees increase in ransomware, botnet attacks – but online scams still pose biggest threat