Former military intelligence officer introduces idea of ‘network resident threats’

The Daily Swig recently caught up with security author Richard Bejtlich, a former military intelligence officer and leader at the US Air Force CERT, to talk nation-state threats, APTs, and the cybersecurity industry’s ongoing use of military metaphors.

Bejtlich currently serves as the principal security strategist at Corelight.

You have a strong background in incident response. What’s your take on nation-state attacks and attribution in the 21st century?

Richard Bejtlich: I do believe that it’s important to identify who is behind various sorts of attacks, depending on how severe they are. But having said that, it means almost nothing that an intruder is [backed by] a nation state.

You can have nation-state intruders who are clumsy clowns, and you have lone actors who are apex intruders and better than anybody else that’s out there.

I don’t care so much about that when I’m designing a technical solution. I don’t care that it’s a nation state because it almost makes no sense to compare the high-end nation state attackers from Russia with the nation-state attackers in, say, Vietnam. There’s a huge gap between those capabilities.

Something that we’ve been talking about is a different term, the idea of a network resident threat, meaning it’s a threat actor who can be a criminal, who can be state-sponsored. It could be an individual, but it’s someone who is making use of your network and sticking around for a while.

Both of those things are important because it differentiates you from things like threat groups who are trying to embed software engineers in your company.

Richard Bejtlich is principal security strategist at Corelight

Richard Bejtlich is principal security strategist at Corelight

Are these ‘network resident threats’ different from advanced persistent threats (APTs)? If so, how?

RB: Yes. The original APT was China. APT code was created by a [retired] colonel in the Air Force named [Dr] Greg Rattray, who’s a friend of mine. And the reason he created it was we couldn't talk about Chinese threat actors and intrusions into US assets without it being a classified situation.

So, he came up with this code term ‘APT’. And people don’t appreciate that the ‘A’ is ‘advanced’, which means that they can operate through a full spectrum of activity, so they can use off-the-shelf open source downloads to hardware inserts that they developed themselves, all the way to attacks on satellites or close access operations with individuals.

That's what APT means: it’s a full spectrum [of capabilities]. When you think about it from that perspective, only a few countries can do that.

We [the US] can do it. Great Britain can do it. Russia can do it. China can do it. Israel, you know, maybe France. It is only a few countries that can actually operate throughout that full spectrum.

What do you think is gained and what might be lost in people’s understanding of things by using military as opposed to other metaphors to talk about cybersecurity?

RB: I was a former US Air Force officer. When I wrote my first books, they were accused of being a little too militaristic. But that’s where I came from, so that’s how I thought.

The problem you get, I think, in the military sense is that people think in terms of ‘offense’ and ‘defense’.

Defense in the military – in the modern sense, at least – is not hunkering down in a bunker or a castle or something like that.

Defense was the dominant form of warfare because you killed the attacker. It’s not because you were in some kind of impenetrable box.

In the cyber world, defense does not mean killing the attackers or repelling them so that they can’t fight again. That’s the reason why defense is such a strong form of warfare, or has been a strong form of warfare probably since the invention of modern firearms.

Someone with a firearm could sit back behind the wall and just kill people who are attacking them.

We don’t do that in cyberspace. The best you can hope for is that the attacker either gives up because they’re frustrated when they can’t figure out how to accomplish their attack, or they don’t have the appropriate vulnerabilities or misconfigurations to exploit.

The only real way you can take an attacker off the field is to arrest them, deter them, or make them your ally.

Does what’s happening in the political world affect what’s happening in cyberspace? According to various sources, tightening sanctions are why North Korea launched attacks against banks and now cryptocurrency exchanges.

RB: I think that the tighter we’ve been on North Korea… they have absolutely turned towards cyberspace as a way to get the currency they need to keep the regime going.

And, you know, there’s even been reports from defectors that the intruders are incentivized to keep a certain amount of the money that they steal.

There’s been some indications that the Trump administration likes using cyber [capabilities]. When they first came into office, they took away some of the restrictions and made it easier to use that capability.

Cyber is seen as kind of a halfway between a kinetic attack and doing nothing. It fits right in there with drone warfare and some of the other stuff that [became the] new levers of power.

Of course, the difficulty with all that is once you start doing that to other people, then you’ve kind of opened the door for it to happen to you, right?

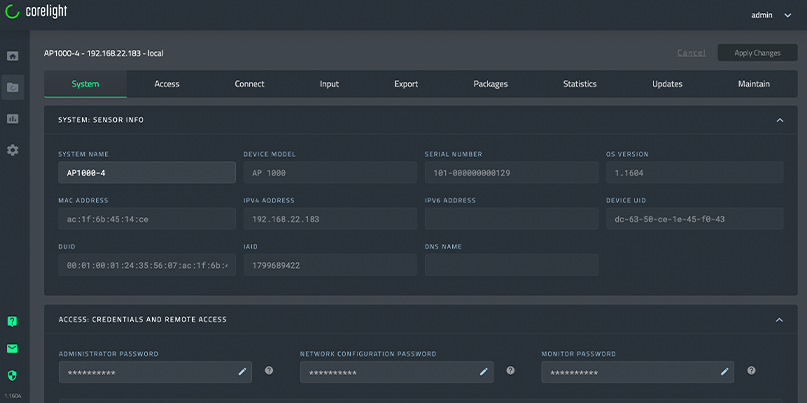

Tell us about your new firm Corelight and the network security monitoring software it produces.

RB: There’s an open source software project that was called ‘Bro’ for many years, beginning in the 90s when it was created by one of our co-founders, Vern Paxson. And it’s continued to be in use by organizations around the world.

A year and a half ago, the project’s leadership team renamed it from ‘Bro’ to ‘Zeek’ because the term ‘Bro’ didn’t seem to fit very well with the advances we’ve had in culture.

It was originally a play on ‘Big Brother’, but even that wasn’t the best idea, I think.

No, I don’t think so either. I mean, I can’t think of any positives from Big Brother. If you’ve read the book 1984 – it’s pretty bloody grim.

RB: As far as what the software did, though, and it continues to do is, it helps you understand what's happening on your network. And the original idea was to try to find anomalies and to let you investigate them and determine if they're suspicious, malicious or benign.

Over the years, the project sort of became more of a neutral tool that allowed users to keep track of what was happening on a network.

And then it's up to a secondary form of analysis, whether that's a person or an algorithm or whatever you want to apply, to decide what you should do next.

Some years ago, the original developers of the software and users of the software decided to form this company, Corelight.

We build products on top of the open source, but we also fund open source development. So, kind of like how IBM was paying for Red Hat development or, you know, Sourcefire was paying for Snort development.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

READ MORE Inside J-CAT – Europol’s Joint Cybercrime Action Taskforce