The Bugcrowd founder discusses the growth of IoT bug bounty programs ahead of a live hacking event at RSA Conference today

Bug bounty submissions for internet of things (IoT) vulnerabilities to Bugcrowd jumped by 384% in 2019 – eclipsing growth elsewhere by a wide margin.

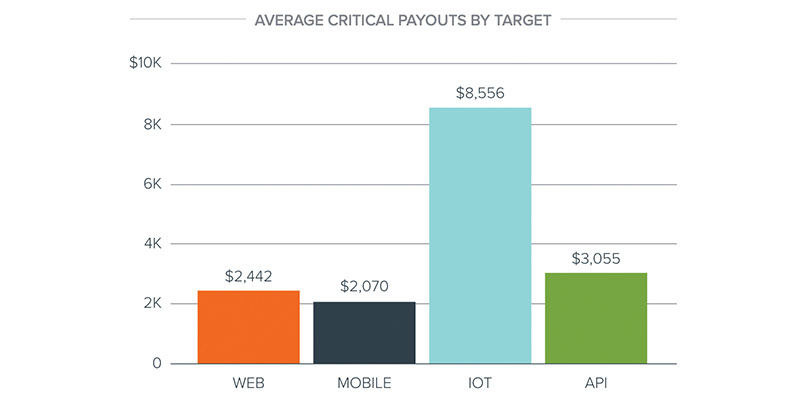

The crowdsourced security platform’s Priority ONE Report for 2019 also revealed that average payouts for critical flaws in IoT devices surpassed $8,500, compared to less than $2,500 for web vulnerabilities.

And if the IoT sector is increasingly lucrative for bug hunters, then it’s a fascinating research area, too, Bugcrowd founder and CTO Casey Ellis told The Daily Swig.

Speaking ahead of a live bug bash at the RSA Conference that focused on Arlo’s smart home products, Ellis reflected on the kind of hackers who are drawn to IoT programs, the ramifications of forthcoming IoT legislation, and Bugcrowd’s wider agenda for 2020.

Hi, Casey. Please tell us a little more about your latest Arlo-focused live hacking event?

Casey Ellis: We have 20 white hat hackers from seven countries, and the goal is to pay out over $100,000 on a particular product. This is actually the second bug bash they’ve done on the system.

Arlo has a privacy pledge, and security is obviously an enabler for privacy, so that’s where we come in: to make sure that those controls are resilient [and] that they can’t be bypassed.

Casey Ellis, Bugcrowd founder and CTO

Casey Ellis, Bugcrowd founder and CTO

Are live events particularly important in the IoT realm?

CE: There’s two reasons to do a live event. One is logistical – if it’s something that is difficult to ship to 50 people then it makes sense.

The other reason is getting the hacker community and [IoT] offense experts in the same room as the engineers and the [vendor’s] security team.

It’s like a turbocharged version of the feedback loop and knowledge transfer that we see every day on Bugcrowd.

There’s no real substitute for face-to-face time. The program owner’s team often walk away with a deeper understanding of the issues and how an attacker thinks and can then design better software.

Despite these benefits, are many IoT vendors still comparatively unfamiliar with, or perhaps suspicious of, hackers?

CE: I think [that mindset is] going away. We were the first to do [IoT programs] back in 2012, when basically everyone was terrified of hackers full stop.

But people have realized that hackers are just normal people with special skills, and we actually need their help.

If there’s still any reticence [around crowdsourced security] then it’s because it’s still a relatively new idea, so it’s our job is to introduce it to [vendors] and get them comfortable with it.

RELATED Bug bounty earnings soar, but 63% of ethical hackers have withheld security flaws – study

What makes IoT research distinct from, say, web or mobile research?

CE: There are fewer bug bounties in play than for web apps and mobile apps, but it’s growing quickly.

With IoT you’re dealing with the entire application stack, [whereas] with web and mobile testing you’re looking at the application as a black box from the outside in, through the API, or whatever else.

With IoT, you’ve got the full operating system, the middleware, interfaces to APIs on the back end. It’s embedded and it’s hardware.

It’s also part of an ecosystem, so the relationships between the device, back end, and so on come into play as well.

It’s a different learning path: hackers are physically manipulating a device as opposed to sitting there looking at a website.

Once you’ve figured out PHP middleware on Linux with a MIPS processor, or some of the more vanilla configurations, that's when people start looking into… more exotic IoT systems.

System combinations on the market are getting quite numerous, so there’s a lot to get good at.

We actually push a lot of IoT 101 training in our LevelUp conferences and Bugcrowd University.

Bugcrowd HQ in San Francisco

Bugcrowd HQ in San Francisco

What kind of hackers does the IoT sector typically attract?

CE: People experienced in thinking about security from an ecosystem standpoint is one persona. They’re thinking about the boundaries of responsibility.

The others I see are folks with a hardware bent, people with an electronics background in radio and networking.

As a class of testing there are similarities with AppSec because, fundamentally, everything is code, right?

Once they realize they can apply hacking and offensive security techniques in that hardware realm, they tend to get hooked quite quickly. I’ve sat with folks doing this and it’s a really interesting subset.

And the payouts are potentially huge, right?

CE: The total payouts in the first quarter of last year doubled year on year.

The average payout was $2,000 per vulnerability across all severities – that’s 78% year-on-year growth. The largest that we’ve had for an IoT device I believe was $140,000.

Some of the larger devices, like connected cars, tend to offer large payouts.

From Bugcrowd’s Priority ONE: The State of Crowdsourced Security in 2019

From Bugcrowd’s Priority ONE: The State of Crowdsourced Security in 2019

There’s a lot of IoT legislation in the pipeline – for instance in the UK, Australia, and from US federal and state governments. What might this mean for bug bounty platforms?

CE: Most IoT legislation I’ve read is baseline: don’t have hard-coded passwords, have update routines that don’t require user intervention…. Things that [remove the] low-hanging fruit and the opportunity for things like Mirai.

I think the scopes might offer an increased reward for anything that violates these regulations.

Speed to market is the natural enemy of security, but you’ve got IoT products being rushed to market. Plus it’s distributed – you’re not just fixing it at one spot like it’s out there in the wild.

Brands like Arlo recognized that trend and wanted to go out to market and say: “Our products are secure, this is how we tested it.”

As consumer awareness of IoT security grows, vendors can demystify who hackers are through events like bug bashes. They can tell the public: “This is security feedback we openly solicit from the internet, and we’re making our stuff more secure as a result.”

An academic paper published last year concluded that bug bounties make an invaluable contribution to IoT security as a last line of defense behind secure-by-design and penetration testing. Do you agree?

CE: I think we really need to disambiguate what people mean by the term ‘bug bounty’. They are usually thinking about a public bug bounty, which definitely is the last line of defense.

But we’ve done bug bashes on pre-production software earlier in the development chain.

Our next generation pen testing is essentially the same model in terms of accessing the crowd but delivered in a far more constrained, focused way.

Calling it a bug bounty would be an oversimplification, but I do think the crowd can be brought in far earlier in the process.

What’s top of Bugrowd’s agenda for 2020?

CE: We have some features coming out to get as many opportunities out in front of people, and create as many opportunities for a match, as possible.

The researcher or hacker can either self-select into a program or, if they haven’t been invited [onto a private program] that they feel they could be useful to, they can join a waitlist. Then we can infer whether their skills are a good fit.

I think bug bounty has illustrated pretty clearly that the internet doesn’t know where its stuff is, so we’re doubling down on attack surface management, which we enhanced this week.

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE Meet the bug bounty platform putting community into crowdsourced security