Do cybercrime laws need reform? In the third episode of SwigCast, we put the UK’s aging Computer Misuse Act under the spotlight

Click play to listen now. Also available on SoundCloud and all major podcast platforms

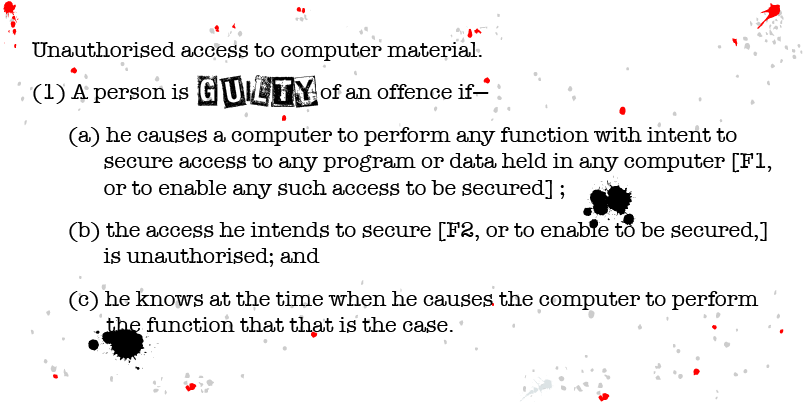

As the UK’s main computer hacking law approaches its 30th anniversary, there’s a campaign afoot to reform one of its central tenants: the concept of unauthorized access.

One of the people heading that campaign is Ollie Whitehouse, chief technology officer at NCC Group and non-executive director at PortSwigger, who joined us for the third episode of SwigCast to discuss the need for – and challenges involved in – getting Britain’s cybercrime legislation updated.

“If you’re a system administrator, and you come across some illegal images, you have a defense written into [inappropriate materials] law so that you can hold onto those images in order to be able to hand them off to the police,” Whitehouse told SwigCast.

“There is today no such defense against any Computer Misuse Act offence,” he said.

“You’re either authorized or you’re not.”

Hack against royalty spawned law

The Computer Misuse Act (CMA) is the foundation of the UK’s criminal laws covering computer hacking and related forms of malfeasance.

The law was introduced in 1990, partly in response to the decision in R v Gold & Schifreen, a case that stemmed from an infamous hack of BT’s view-data Prestel system.

Schifreen was one of the computer enthusiasts who tried to demonstrate that the Prestel system was insecure, eventually gaining access to the personal message box of Prince Phillip in order to prove their point. These hijinks embarrassed BT and resulted in a criminal prosecution.

“Back in those days [in the early 1980s] there was mainly theft of electricity, which was what people got charged with if they were doing phone phreaking,” he told SwigCast.

“There was no legislation to do with computers and hacking and unauthorized access to computers.”

Schifreen, along with Steve Gold, were prosecuted under laws covering forgery, initially convicted and fined, but later acquitted on appeal when senior judges ruled that counterfeiting laws were misapplied in the case.

Both hackers unwittingly became key players in forging the UK’s computer crime law.

Private sector joins forces

Fast-forward to 2019 and Whitehouse is helping to lead a campaign to bring the legislation into the modern digital era.

“When we look at [the CMA], we need to remember that it was written in 1990,” Whitehouse said.

“Quite simply, it didn’t necessarily foresee the internet in its current guise,” he added.

Since its inception the CMA has criminalized “unauthorized access” but this measure has becoming increasingly problematic because it makes it difficult to offer threat intelligence services.

This has prompted NCC Group to get together with rivals Context [Information Security], Nettitude, and Digital Shadows to lobby for changes to the law.

The current CMA regulations are impeding efforts by private sector firms to help the UK government, they argue, and hindering Britain’s leading position as threat intelligence provider.

“The government is expecting the private sector to help in the fight against cybercrime,” Whitehouse explained.

“At the moment we are doing that with both arms tied behind our back and a blindfold on because we’re precluded form supporting them in [all] the ways that we could,” he said.

There have been two major revisions to the CMA in its 30-year history, but these changes have so far failed to address areas of concern to UK tech firms.

“The revisions have only added things, they’ve never weakened anything,” Whitehouse explains during the podcast.

“They’ve added new crimes, or clarified particular crimes, but they’ve never adjusted, weakened, or provided a defense.”

Shodan low-down

In addition, British tech firms operating under the law are constrained from developing tools like Shodan, an IoT search engine whose operations are permitted under comparable US laws.

Reforming the law so that UK-based tech firms are free to develop a greater range of technologies and aid the authorities ought not to introduce loopholes in the legislation that criminals might be able to exploit, Whitehouse cautioned.

“I think that [Shodan] is a good example of one of the bigger discrepancies between the UK and the US [laws] but similarly they [both] very clearly criminalize illegal hacking and the provide a way for legislators and law enforcement officials to prosecute under those,” he said.

“The challenge for any reform is that everyone is anxious about are [if] you going to give the bad person a defense which they could use. They [criminals] are trained professionals, and they try to use the statuary defences of a way of getting out [of trouble].”

Revision time

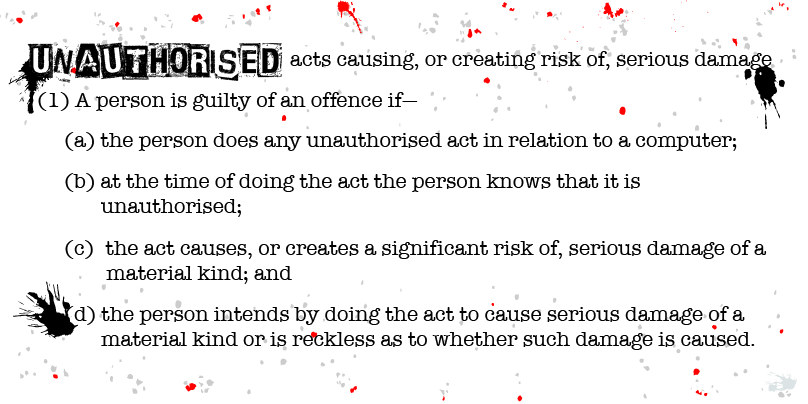

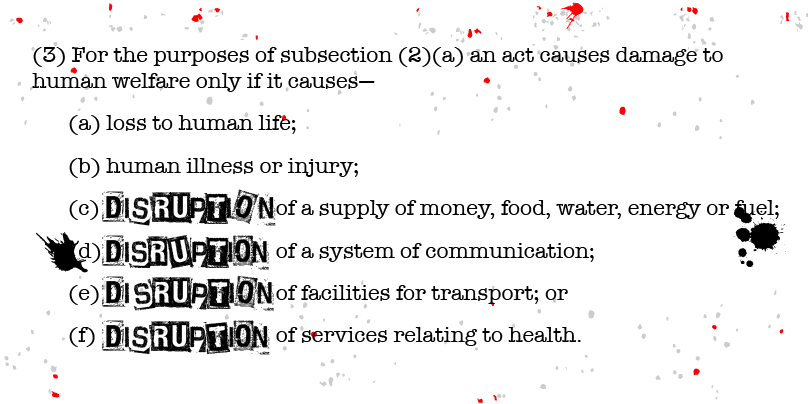

The Computer Misuse Act 1990 [non-HTTPS link] has been amended by the Police and Justice Act 2006 [non-HTTPS link], which increased the maximum sentence of imprisonment for breaching the Act and made denial of service attacks (which up to then had been a grey area of the law) clearly criminal.

The Serious Crime Act 2015 made computer misuse that caused serious damage punishable by up to 14 years in prison or a fine or both, extending up to a potential sentence of life imprisonment where national security or human welfare gets endangered.

UK legislators have taken expert witness from computer scientists and industry experts in developing the law.

On occasion proposed measures have been tabled that could have a detrimental effect on common industry practice. For example, at one point it was suggested that possession of “computer hacking tools” should be criminalized.

Critics at the time said the proposed measured “outlawed” dual use tools such as Metasploit that are widely used in penetration testing and other legitimate security functions. These measures were dropped.

Still a relatively new area of criminal law, statistics related to CMA charges and convictions tend to be a bit patchy.

According to the UK’s Office for National Statistics, there were an approximate 4.5 million cybercrimes committed in England and Wales last year – 3.2 million were reported as fraud, and approximate 1.2 million were related to computer misuse.

A Freedom of Information request obtained by The Daily Swig reveals that there were 169 convictions under the CMA between 2010 and 2015.

Additional reporting by Catherine Chapman.

SwigCast is a regular podcast that puts a variety of infosec topics under the microscope. Catch up and listen to previous episodes