For all of the advancements that have been made in encryption and anonymization technology, basic operational security oversights remain a key factor in darknet market takedowns

Over recent years, law enforcement agencies have combined efforts internationally to tackle the biggest illicit markets to ever exist on the dark web.

From the notorious Silk Road to smaller copycat sites, the drive to shutdown these operations has so far been deemed a success.

The causes of these closures are vast and varied. However, for all of the advancements that have been made in encryption and anonymization technology, basic operational security (OpSec) oversights remain a key factor in darknet market takedowns.

The OpSec mistakes that led to the demise of several leading darknet markets were outlined in a talk at BSides London last week.

John Shier, senior security advisor at Sophos, explained that darknet sites that mainly trade in drugs and various illicit services come and go for various reasons.

On occasion, marketplace founders can steal funds held in escrow before scarpering (a so-called ‘exit scam’).

Sometimes, sites can be forced offline or taken down as the result of denial-of-service attacks or intractable security vulnerabilities.

And just like their real-world counterparts, law enforcement action is also a hazard for the operators of darknet cybercrime bazaars.

Shier’s talk, ‘Closed for Business: Taking Down Darknet Markets’, focused on the story behind Operation Bayonet – the seizure and subsequent takedown of AlphaBay and Hansa in July 2017.

Alpha to Omega

AlphaBay launched in Sept 2014, around a year after the closure of its forerunner, Silk Road. Almost three years later, AlphaBay was 10 times the size of its predecessor, with more than 200,000 users and 40,000 vendors.

Prior to its takedown, AlphaBay held more than 250,000 listings for illegal drugs and toxic chemicals, and more than 100,000 listings for stolen and fraudulent identification documents and access devices, counterfeit goods, malware and other computer hacking tools, firearms, and fraudulent services.

Transactions were paid in bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

The marketplace had built itself a trusted reputation, but the foundations were shaky due to OpSec mistakes dating back to its inception.

These failings allowed police to identify Alexandre Cazes, a Canadian national resident in Thailand with a Thai wife, as a suspect. In July 2017, they raided his home.

Cazes, 26, was found dead in his cell in Thailand several days after his arrest. Suicide is suspected.

RELATED The long road to freedom: What’s next for Silk Road founder Ross Ulbricht?

Cazes made the mistake of using his personal Hotmail address as the ‘from’ address in AlphaBay’s automated welcome and password reset emails in the months after the service began.

He used the same email address in running a legitimate Quebec-based computer retail business. A PayPal account run by Cazes listed his Hotmail account and an email address linked to the retail business as the contact details.

In addition, Cazes was said to have used a pseudonym to run AlphaBay that he’d previously used on carding and technology forums.

These clues allowed authorities to identify Cazes as a suspect. In mounting an arrest operation, police monitored the site and created an artificial system failure so that they could arrest him whilst he was in the process of rebooting the AlphaBay server.

Shier explained how police tricked Cazes into abandoning this task by staging a car accident outside his Thai villa.

Undercover cops crashed a car through his front gate after supposedly making a mess of a three-point turn, as shown in a video clip of the incident obtained by Motherboard at a cybersecurity conference.

The tactic allowed police to recover Cazes’ unencrypted laptop while it was unlocked and logged into AlphaBay’s systems. The unlocked laptop also offered police a catalogue of illicit assets to target for seizure.

Stirring the moneypot

The closure of AlphaBay created a gap for other eBay-style underworld marketplaces. Hansa, an online darknet market that operated as a hidden service of the Tor network, seemed poised to fill it.

Many AlphaBay denizens did indeed migrate to Hansa, although they were unaware that the site had also been hijacked by law enforcement,

Dutch police seized development servers related to Hansa following a tip from a security researcher a year earlier, just weeks before the demise of AlphaBay.

Old IRC chat logs were recovered from the system, and cops began monitoring the site. The administrators realized that something was amiss and moved the site over to an initially unknown host.

This was meant have been the end of the trail, but police got another break in April 2017, Shier explained, leading them to identify to site’s hosting firm, based in Lithuania.

German police arrested two alleged Hansa administrators, aged 30 and 31, in June 2017, while Dutch police were able to seize control of the site and to impersonate its administrators.

As with the AlphaBay case, police ran a sting so that they could arrest the Hansa administrators whilst they were logged into systems.

(The same tactic was used in the earlier arrest of Silk Road admin Ross Ulbricht. Agents staked out Ulricht, following him to a library before staging a fake fight to distract him, allowing another agent to seize his laptop while he was still logged on.)

Police in Europe worked with the FBI and coordinated their actions so that they were able to lay a trap for miscreants fleeing the imminent AlphaBay shutdown.

The plan worked almost too well, with police obliged to suspend Hansa sign-ups at one point, after systems struggled to keep up with the influx.

After the arrest of the administrators, Hansa’s servers and their infrastructure were seized, and an exact copy of the marketplace was transferred to Dutch servers.

“The German admins were arrested when they were online, with their PC unlocked and unencrypted,” Shier told BSides London attendees. “Police were able to take over systems without any downtime. Police knew they [admins] were online because they were monitoring traffic.”

Dutch police had turned Hansa into a honeypot – buyers and sellers could still access the darknet site, blissfully unaware that their every action was being recorded by cops.

User passwords and supposed PGP-encrypted chats were recorded in plaintext.

In addition, the marketplace’s automatic photo metadata-stripping tool was bugged, allowing police to collect geolocation data for drug listings.

Police claimed that the marketplace’s photo database had been lost as a trick to get vendors to re-upload photos, handing over intelligence to law enforcement in the process.

Other social engineering trickery was used to get users to download files that gave away their IP address.

All of this, in addition to allowing illegal transactions to run through the seized marketplace, allowed police to collect evidence against Hansa’s merchants before the shutters were brought down on the site in late July – around five weeks after it was taken over.

RELATED New facial recognition tool lifts the lid on your social media presence

While these sites are no longer operational, OpSec fails involving darknet drug dealers have continued, Shier added.

For example, Dream Market dealer-turned-administrator Gal Vallerius was arrested in August 2017, after a border search of his laptop uncovered credentials linked to Dream Market, a PGP key entitled ‘OxyMonster’, and a cache of $500,000 in bitcoin.

Investigators reportedly unveiled Vallerius’ real identity through his bitcoin transactions.

The French-Israeli was arrested in Atlanta, US, en route to the World Beard and Moustache Championships in Austin, Texas.

He was jailed for 20 years last October after admitting various drug trafficking and money laundering offences.

Shier also mentioned how the German administrators of Wall Street Market, another darknet marketplace, gave away their real IP address when logging into the site’s server infrastructure even though their VPN service was playing up.

Switching channels

There are myriad ways that underground drug lords might be undone, so it’s perhaps no surprise that threat intel agencies including Digital Shadows are reporting that some miscreants are switching to encrypted chat channels in order to trade illicit goods.

In a study into the darknet economy sponsored by security vendor Bromium and released last week, Dr Michael McGuire of Surrey Crime Research Lab discovered that vendors of malware and cybercrime services are also “turning to encrypted messaging services to thwart law enforcement”.

Dr McGuire said his team discovered a shift towards an ‘invisible net’ – invitation-only forums, private messaging, and encrypted apps like Telegram, WhatsApp, and Wickr, where interactions between members are thought to be better shielded from law enforcement.

“In fact, 70% of dark net service providers invited our undercover researchers to talk over private, encrypted channels in the ‘invisible net’,” he writes. “This is making it harder than ever for law enforcement to track darknet transactions and for enterprises to defend themselves.”

Darknet marketplaces of various types remain in operation alongside a bewildering array of alternatives.

Viktoria Austin, strategy and research analyst at Digital Shadows, explained: “It’s a really shifting space at the moment. New markets keep appearing, then they disappear – which is causing chaos.

“Whilst markets are being disrupted by law enforcement, we also see markets conducting exit scams, which further diminishes trust. An example of this is the Olympus marketplace.”

Austin added: “The current main darknet markets currently include: Empire (English language), Dark Shades, Market.ms (Russian language), Tochka, FDW market (French language).

“It’s quite a complex scene, cybercriminals aren’t just migrating to one service, such as Telegram – rather they’re utilizing anything that’s available to sell, which includes markets, chat services, paste sites, open AVCS sites such as Shoppy and Selly.

“But that doesn’t tell the whole story, as where actors buy and sell depends on geography. For example, we may see Russian cybercriminals begin by selling on a forum, but then they may switch to Jabber (chat service).”

“Factors that are influencing cybercriminal activity on darknet markets depend on level of trust. For example, markets with escrow and 2FA [two-factor authentication] typically garner a higher level of trust from users,” she added.

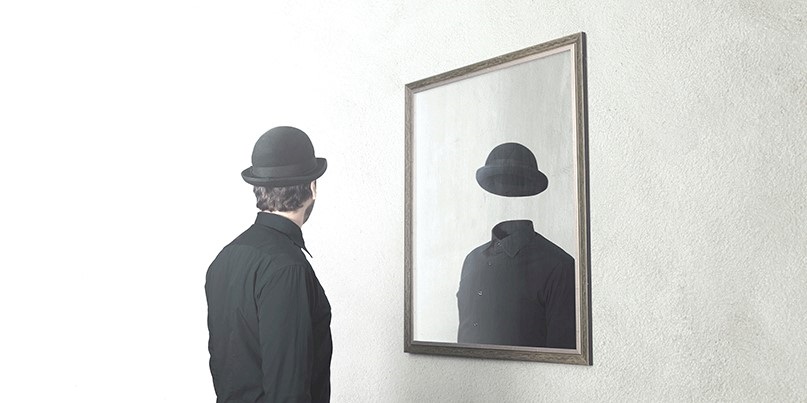

Dual identities

This is a tale of those who got caught and what led to their undoing.

Its lessons are applicable to more than just illicit drug dealers, but to others such as human rights activists and journalists that may need to make use of the dark web for communication. The key message?

“If you have dual identities [on the dark web and clear web], then don’t mix them up,” Shier concluded.