The persistence of cumbersome legacy approaches is more problematic than ever, says the former Apache Maven chair

Founded in 2008, Sonatype has been instrumental in popularizing the DevSecOps paradigm through its flagship open source repository manager, Nexus Repository, among numerous other software development tools.

From the online All Day DevOps conferences to its DevSecOps community and software supply chain reports, the company has also led the conversation around overcoming application development hurdles.

Brian Fox, the company’s co-founder and chief technology officer, has been a key figure in both Sonatype’s success and in promoting the adoption and optimization of DevSecOps practices by millions of developers worldwide.

In this interview, the former Apache Maven chair talks about how the persistence of cumbersome legacy approaches is more problematic than ever, with malicious actors increasingly targeting applications, becoming faster at exploiting vulnerabilities, and planting malicious components in open source libraries.

Have organizations become more effective at securely managing open source components since you founded Sonatype?

Brian Fox: In the early days, people weren’t even aware [of the risks]. Developers would say they had a firewall, and their security team would do static code scanning without realizing that they were missing the open source [components].

The legacy approaches just weren’t well suited to dealing with the new problems. But many companies still don’t have that list of all the open source components they’re using. So, when something happens, they can’t answer the simple questions: Am I affected? If so, where and when? How do I track the remediation?

When there’s a problem with your car, we expect manufacturers to know all the parts that went into it and be able to do a recall of affected vehicles. But software doesn’t have the same level of due diligence.

Brian Fox

Why do you think organizations persist with these legacy approaches?

BF: There are a couple of problems. Technology leaders cut their teeth before open source binary reusability, so the mental model is: “My developers are writing code, so I need to stay with that code and make it better”.

This ignores the risk in the open source and third-party dependencies.

The other challenge we see is security teams running scans after the fact, and by the time they detect a [problem], it’s already baked into the product.

The development team is trying to go as fast as they can because innovation is king, and then the security guy comes along later to hold everything up.

With security and development there is still this tribal ‘us versus them’ mentality.

If [the security team] tells me that I have to go and replace that component, then it’s their fault that we’re six weeks late. It stops organizations, I think, from getting their arms around [the problem].

What does a best practice approach to fast, innovative, secure application development look like?

BF: The Etsy model of pushing many releases quickly means you can fix bugs like memory leaks quickly.

Then security vulnerabilities kind of look like regular bug fixes. There doesn’t have to be any drama. “Maybe we can’t prove that this is exploitable, but it’s dangerous. Let’s just update because the updates are easy anyway.”

Both sides win.

But if you try to maintain the silos and legacy approval processes, people charge into it and focus on the technology [not the processes].

Like, how will I automate my builds? How will I automate my deployments? And then legal [still wants] the six-week turnaround for approval, or security comes in at the end, it blows up the whole DevOps process.

So, you need to automate those policies to realize the promise of a truly DevOps or continuous delivery approach.

The legal team, the security team, the developers – they all have important functions. So, let’s figure out how everybody can achieve their goals.

The Sonatype team at DevSecCon in Singapore

The Sonatype team at DevSecCon in Singapore

What kind of cumbersome open source processes was Nexus designed to improve?

BF: Nexus was very much considered a dev only tool, but as DevOps came along and containers became a thing, it was pushed into a continuous delivery [model] and a niche thing became more mainstream.

Between, say, 2007 to 2012, big companies would have a big, manual workflow and lump open source components into the same process as deciding to move to Linux or OpenOffice.

The net effect was either the company was really good at holding developers to that process and inadvertently harming innovation, or they weren’t, and nobody followed the process anyway.

It was impossible to keep up the speed of development and pull in all these new components constantly.

Many people are still using Struts 1 because it’s on their approved list and it’s too much work to get approval for something new. So, the workflow that’s intended to make things safer inadvertently incentivizes the wrong behavior, and now they’re stuck on a 10-year-old framework for which there are no updates.

Several organizations were recently attacked within a few days of the public disclosure of security flaws in SaltStack, the infrastructure automation platform. What does this tell us about the perils of public disclosure?

BF: Back in 2006, it was 45 days from vulnerability disclosure to an active breach.

Then with Equifax [in 2017] it was three days. The zero-day disclosure happened, the Apache project fixed it and announced it – they did all the right things. But then companies didn’t upgrade fast enough.

The bad guys can turn exploits around quicker than many companies can fix their issue.

I think SaltStack is just the most recent replication of the same pattern. Vulnerabilities occur in software. We’re going to make mistakes.

Saltstack pre-announced that a vulnerability was coming, and that internet-facing instances should be locked down. I’m sure it was a tough decision on how to handle this communication.

On the one hand, you’re potentially tipping your hand to the bad guys, but on the other, by simply making their stuff not internet available [organizations] can sidestep the exploits.

Read more of the latest open source software security news

I’m sure there are probably still [SaltStack users] out there who haven’t got the message yet.

Users are used to the procurement model, where they buy this thing from a company and expect them to provide updates. But then they also often have thousands of open source components and they don’t think about that same process.

More recently, bad guys also started creating problems themselves, using typosquatting and other techniques to publish malicious OS components.

It was getting increasingly sophisticated. In some cases, they were choosing the target, figuring out which projects they depended upon, then social engineering their way in to create malicious code.

And once the payload was delivered, they were able to cover their tracks.

If the security guy is playing inspector cop at the very end of the process when you cut a release, it’s too late because your developers and development infrastructure is now the target.

So, you need to understand what you’re using, make those good choices, and turn around that response quickly.

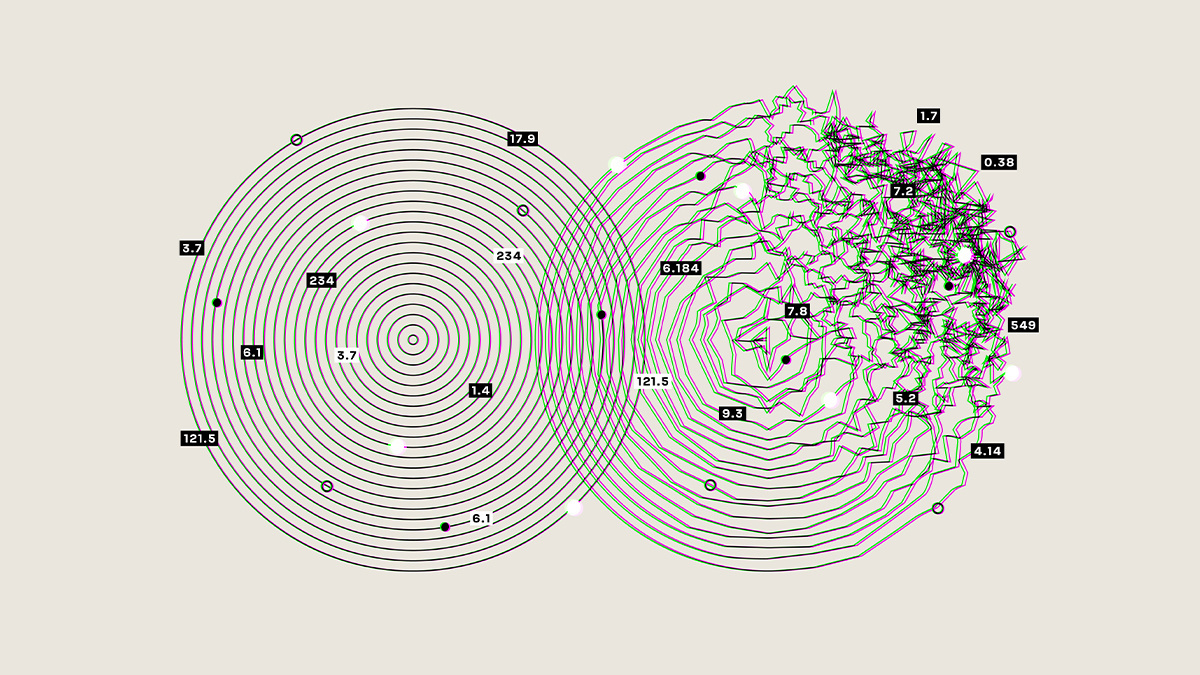

Running scans late in the development stage can mean security issues are already baked into the product

Running scans late in the development stage can mean security issues are already baked into the product

How can the industry combat the emergence of malicious open source components?

BF: So, from an open source perspective, we’re looking at the history of a particular project. Who is doing the releases and when? What types of dependency changes are typical at any time?

Why would a popular project jam a random garage band dependency that no one else is using into their project?

If something pops out of the norm, we have tools to temporarily or permanently stop downloads.

The changes themselves may not in fact be malicious, but the entropy is higher, therefore it’s riskier to adopt this component.

If this guy has never released [a component] before, the chances that he screwed something up are much higher than the guy who has done the last 50 releases.

You don’t have to consider the security dimension as a cost center. You need some guard rails, but if you do it intelligently, you can make better software, faster – and [when there is a security flaw], you can turn it around faster.

Everybody wins, but not enough people are thinking about the problem that way. It’s still very much my budget versus your budget. Developers want a tool, security wants a tool – they’re fighting over it, right?

How have attackers’ tactics evolved in recent years?

BF: As open source became more prevalent, the bad guys started to recognize the [rewards of targeting the] ‘common mode failure’: “everybody’s using this component, so if I can find a vulnerability, then I’m golden.”

For example, if they figure out how to attack Struts then they can use Google to search for anybody using Struts, because the patterns are recognizable in the URL.

You can get yourself an attack list and automate against that pretty easily, so that shifted the attack model. And because people got better at perimeter defense, a [2016] Verizon report showed that attacks were shifting towards attacking web applications, because the common mode failure existed across all of them.

These new attacks also take advantage of the fact that people will auto update when there’s a new version.

So, there’s been an evolution from using known attacks to break unknown code, to breaking the known code and finding a whole bunch of unknown people to attack.

The Department of Defense was being probed by the same exploit that ultimately got Equifax hacked. It seems likely that somebody was just targeting everything.

READ MORE Shodan founder John Matherly on IoT security and dual-purpose hacking tools