Published: 10 December 2025 at 12:32 UTC

Updated: 21 January 2026 at 10:34 UTC

This post shows how to achieve a full authentication bypass in the Ruby and PHP SAML ecosystem by exploiting several parser-level inconsistencies: including attribute pollution, namespace confusion, and a new class of Void Canonicalization attacks. These techniques allow an attacker to completely bypass XML Signature validation while still presenting a perfectly valid SAML document to the application.

You can get this paper as a print/download friendly PDF. You can also grab the slides from Black Hat.

Here’s a demo of the attack on a vulnerable GitLab EE 17.8.4 instance:

Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML 2.0) is a complex authentication standard built on insecure and outdated XML technology. These legacy foundations have made the protocol notoriously difficult to maintain and have resulted in a persistent stream of critical vulnerabilities over the past two decades.

This paper introduces several novel classes of Signature Wrapping (XSW) attacks capable of completely bypassing authentication in widely used open-source SAML libraries used across the internet.

In addition, I present an open-source toolkit designed to identify and analyze discrepancies between XML parsers - enabling the discovery of authentication bypasses with very few requirements.

The recent increase in SAML vulnerabilities shows that secure authentication cannot happen by accident. Keeping protocols like SAML safe requires coordinated, ongoing effort from the entire security community, not just quick fixes.

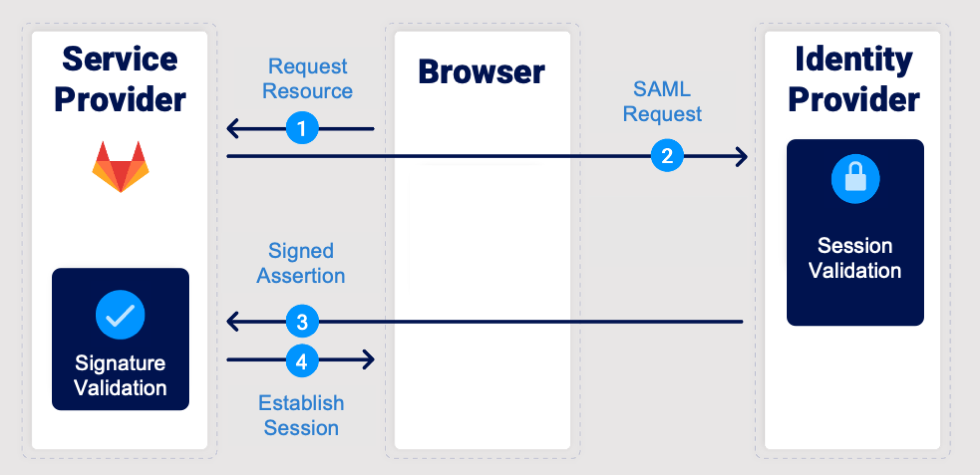

The Service Provider-Initiated (SP-Initiated) SAML flow is the most common way users authenticate through SAML. It starts when a user tries to access a protected resource on the service provider’s website. Since the user is not yet authenticated, the service provider generates a SAML authentication request and redirects the user to the Identity Provider (IdP) for verification.

The IdP receives this request, verifies its validity, and then issues a SAML Response containing a digitally signed Assertion that confirms the user’s identity. This response is sent back via the user’s browser to the service provider (SP). The SP then verifies the digital signature and extracts user information (such as username and email) from the Assertion. If the signature and data are valid, access is granted.

The overall security of this flow depends entirely on how the SAML Response signature is validated. In many implementations, signature verification and assertion processing are handled by separate modules or even different XML parsers. An XML Signature Wrapping (XSW) attack exploits the discrepancies between these components.

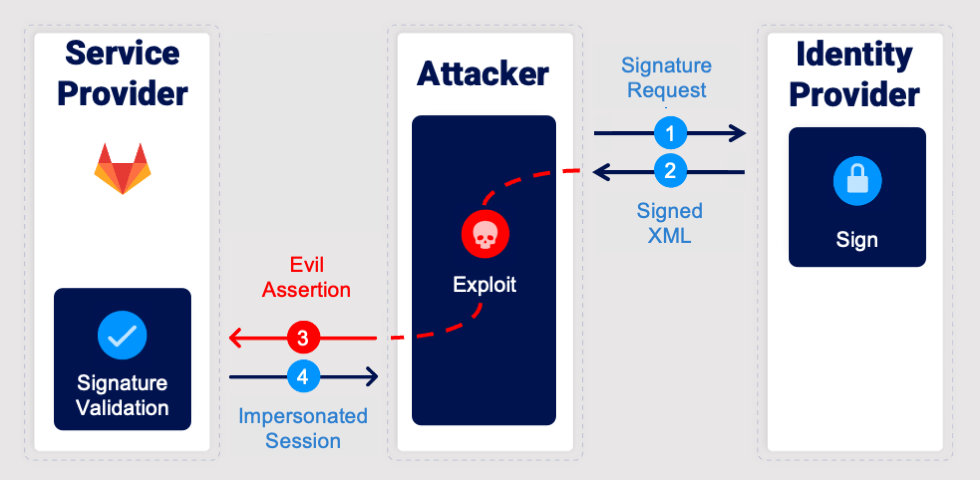

In a typical scenario, an attacker intercepts a legitimate SAML Response signed by a trusted Identity Provider and injects a new malicious Assertion containing arbitrary user information into the same document. When the Service Provider processes the response, the signature verification module correctly validates the legitimate portion of the message, while the SAML processing logic mistakenly consumes the attacker’s injected Assertion. As a result, the attacker’s forged data is treated as authentic, leading to a privilege escalation.

Juraj Somorovsky, in his research "On Breaking SAML: Be Whoever You Want to Be" suggests that this could be done by registering through the IdP, performing a man-in-the-middle attack, or even digging through publicly exposed files using Google dorking. The problem is that this is a big requirement. Getting a valid signed SAML Assertion for an arbitrary website is extremely difficult. Identity Providers almost never expose them, and even if you somehow capture one, most Service Providers will accept it only once, after that it gets cached and rejected.

So we take a different approach. Instead of trying to steal or reuse a signed Assertion, we simply reuse any other XML document signed with the IdP’s private key.

With that legitimate signature in hand, we can then exploit the server's flawed signature-verification logic and make it believe that our malicious Assertion is the one that was signed, even though it wasn’t.

In our previous research with Gareth Heyes - SAML roulette: the hacker always wins, we demonstrated how flaws in handling Document Type Declarations (DTDs) could be exploited to perform an XSW attack against the widely used Ruby-SAML library. To mitigate these issues, two security patches were released - versions 1.12.4 and 1.18.0.

In this paper, I use the Ruby-SAML 1.12.4 patches as a case study to demonstrate why incremental fixes are insufficient and despite multiple attempts to address XML-related vulnerabilities, the underlying architecture remains fragile.

Security patch 1.12.4 introduced two new checks to ensure that the SAML document does not contain DTDs and is a well-formed XML document. While this eliminated our original exploit, it did not address the root cause of the problem. The XML Security library still relied on two separate XML parsers - REXML and Nokogiri - for different parts of the validation process.

According to the SAML specification, the Assertion element - or one of its ancestor elements - must be referenced by the Signature element, using an enveloped XML Signature.

In the Ruby-SAML implementation, both REXML and Nokogiri locate the Signature element using the XPath query "//ds:Signature", which retrieves the first occurrence of a signature anywhere in the document. After that, additional logic, implemented in REXML, verifies that the parent element of the signature is an Assertion. This overly permissive XPath query became a key component of the exploit.

An XML Signature is a two-pass signature mechanism: the hash value of the signed resource (DigestValue) and the URI reference to the signed element are stored inside a Reference element. The SignedInfo block that contains these references is then itself signed, and the resulting Base64-encoded signature is placed in the SignatureValue element. In the Ruby-SAML implementation, REXML is used to extract the DigestValue, which is then compared against the hashed element transformed with Nokogiri. The SignatureValue, also extracted by REXML, is expected to match the SignedInfo element as processed by Nokogiri, creating a fragile dependency between two different parsers with inconsistent XML handling.

To craft a reliable exploit, it is important to first understand a fundamental feature of XML - namespaces. XML namespaces provide a mechanism for qualifying element and attribute names by associating them with Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs).

Namespace declarations are defined using a special family of reserved attributes. Such an attribute’s name must either be exactly xmlns (to declare a default namespace) or begin with the prefix xmlns: (to define a namespace with a specific prefix). For example:

<Response xmlns="urn:oasis:names:tc:SAML:2.0:protocol"/><samlp:Response xmlns:samlp="urn:oasis:names:tc:SAML:2.0:protocol">

Both forms are valid and associate elements with the same SAML 2.0 Protocol namespace.

Namespaces are ideal for Signature Wrapping attacks, as they directly influence how XML elements are identified by XPath queries. Most SAML libraries rely on libxml2 for XML parsing. This library inherits numerous legacy quirks.

A great demonstration of libxml2’s fragility is found in Hakim’s "Abusing libxml2 quirks to bypass SAML authentication on GitHub Enterprise (CVE-2025-23369)", which showcases how internal caching behavior can be abused for unexpected XML processing results. Unfortunately, since both Entities and Doctypes are now restricted by 1.12.4 patch, that particular attack vector is no longer viable - forcing us to explore alternative ways to exploit parsing inconsistencies.

One helpful insight comes directly from the libxml2 documentation of xmlGetProp:

This function looks in DTD attribute declarations for #FIXED or default declaration values.

NOTE: This function ignores namespaces. Use xmlGetNsProp or xmlGetNoNsProp for namespace-aware processing.

Both Ruby (Nokogiri) and PHP expose libxml2 behaviors that can desynchronize signature verification from assertion parsing. In Nokogiri, attribute lookups such as node.attribute('ID') (not a get_attribute) or the shorthand node['ID'] ignore attribute namespaces and use only the simple name. When multiple attributes collide by simple name (e.g., ID and samlp:ID), only one is returned, and the documentation does not guarantee which one.

In PHP’s DOM: DOMNamedNodeMap::getNamedItem also retrieves an attribute by simple name only.

This ambiguity can be directly observed in how parsers resolve attributes. Consider the following two equivalent-looking XML fragments:

<samlp:Response ID="1" samlp:ID="2"> # 1<samlp:Response samlp:ID="2" ID="1"> # 2

In the first case, the call xmlGetProp returns 1, while in the second case it returns 2.

The difference depends solely on the attribute order within the element - behavior inherited from libxml2. Because the namespace is ignored and the returned attribute is undefined when duplicates exist, developers have no control over which attribute is selected.

REXML, which implements its own XML parsing logic independent of libxml2, is vulnerable to the same attribute pollution issue. Both attributes['ID'] and get_attribute("ID").value show inconsistent behavior depending on namespace handling.

<Response ID="1" samlp:ID="2"> # 1<samlp:Response ID="1" samlp:ID="2"> # 2

In the first case, the access to the attribute by attributes['ID'] returns 1, while in the second case it returns 2. When a namespace prefix is present, REXML’s internal lookup treats attribute names differently, leading to the opposite selection order compared to libxml2. This inconsistency means that the same XML document can produce different attribute values across parsers, allowing an attacker to manipulate which element is actually signed versus which one is processed:

<samlp:Response ID="attack" samlp:ID="ID">

<Signature>

<Reference URI="#ID"/>

</Signature>

<samlp:Extensions>

<Assertion ID="#ID"/>

</samlp:Extensions>

<Assertion ID="evil"/>

</samlp:Response>

Attack Workflow

As you already know, xmlns is a reserved attribute, and xml is another reserved prefix. Both are defined by the XML specification and cannot be redeclared or bound to different values.

However, in REXML, these are treated internally as a regular attribute. This subtle difference creates a significant weakness. By redefining or injecting namespace declarations, an attacker can manipulate how namespace-aware XPath queries behave, causing REXML to resolve elements that other parsers - such as Nokogiri - ignores correctly:

<Signature xml:xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#'/>

This technique also works in the opposite direction, allowing an attacker to hide the legitimate Signature element from the REXML XPath query "//ds:Signature" while keeping the document valid. By carefully nesting elements and redefining namespaces, it becomes possible to make the Signature node visible to Nokogiri but invisible to REXML:

<Parent xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#'>

<Child xml:xmlns='#anything'>

<Signature/>

</ Child>

</Parent>

This allows the attacker to split signature detection logic, causing the parser to locate and validate a Signature element in an unintended location within the document.

Now that we can craft a valid XML document that produces two different interpretations in REXML and Nokogiri, the next step is to determine where to inject malicious elements without violating the XML Schema.

The XML Schema Definition (XSD) specifies the syntax and semantics of all XML-encoded SAML protocol messages. In the case of Ruby-SAML, the implementation ships with twelve XSD files, including protocol-schema.xsd, which define the structure and constraints for each element in a SAML Response.

However, XML Schema validation alone does not prevent the inclusion of malicious extensions. A full list of all identified extension points is provided in the supporting materials. Among them, two elements satisfy the key requirement of appearing before the Signature element within a valid SAML Response: the Extensions element and the StatusDetail element. I will use Extensions:

<samlp:Response>

<samlp:Extensions>

<Parent xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#">

<Child xml:xmlns="#other">

<Signature>

<SignedInfo>REAL SIGNATURE</SignedInfo>

</Signature>

</Child>

</Parent>

</samlp:Extensions>

<Assertion>

<Signature>

<SignedInfo>FAKE SIGNATURE</SignedInfo

</Signature>

</Assertion>

</samlp:Response>

At this stage, we can successfully bypass the SignatureValue verification, but the process fails with an invalid DigestValue. The reason lies in how Nokogiri handles canonicalization and digest calculation. During digest computation, the parser temporarily removes the Signature element before calculating the hash, ensuring the signature is not included in the data being signed.

However, in our modified document, the fake Signature element remains inside the Assertion, meaning the parser now attempts to calculate the digest over a string that already contains the signature data itself. This creates a recursive dependency - the digest must include its own hash value - achieving a valid DigestValue in this scenario would require generating a perfect hash collision.

To solve this seemingly impossible problem, we need to take another close look at the SAML specification. According to the standard, the referenced element must be processed through one or more XML transformations before being hashed. By targeting this transformation stage, we open the door to a new class of attack - what I call Void Canonicalization.

Canonicalization defines a consistent way to represent XML documents by standardizing details such as attribute order, whitespace, namespace declarations, and character encoding. This process ensures that two logically identical XML documents produce the same canonical byte stream, allowing reliable digital signatures and comparisons.

Some aspects of canonicalization - such as whether XML comments are included or excluded - have already been exploited in previous Signature Wrapping (XSW) attacks (SAMLStorm: Critical Authentication Bypass in xml-crypto and Node.js libraries). However, beyond these known vectors, there are deeper limitations within the canonicalization process itself that can be abused.

Let's take a look at XML Signature Recommendation, which explicitly warns about the dangers of relative URIs:

Limitations: the relative URIs will not be operational in the canonical form.

The processing SHOULD create a new document in which relative URIs have been converted to absolute URIs, thereby mitigating any security risk for the new document.

This behavior introduces an opportunity: if the canonicalization process encounters a limitation, such as an unresolved relative URI, it may return an error instead of a canonicalized string. Fortunately for an attacker, only a small number of XML parsers are designed to properly handle such failures. Most implementations silently continue execution, treating the missing output as an empty or “void” canonical form, effectively skipping the data that should have been included in the digest. This powerful inconsistency becomes the foundation of the Void Canonicalization attack class.

To demonstrate this behavior, consider the following SAML Response that exploits the canonicalization weakness:

<samlp:Response xmlns:ns="1">

<samlp:Extensions>

<Parent xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/09/xmldsig#">

<Child xml:xmlns="#other">

<Signature>

<SignedInfo>REAL SIGNATURE</SignedInfo>

</Signature>

</Child>

</Parent>

</samlp:Extensions>

<Assertion>

<Signature>

<SignedInfo>EMPTY STRING DIGEST VALUE</SignedInfo

</Signature>

</Assertion>

</samlp:Response>

Here, the declaration xmlns:ns="1" defines a relative namespace URI. It is still a well-formed XML document, but this causes an error during libxml2 canonicalization.

Instead of failing securely, Nokogiri canonicalization implementation simply returns an empty string when this error occurs. As a result, the subsequent DigestValue calculation is performed over an empty input, producing a valid hash of an empty string (47DEQpj8HBSa+/TImW+5JCeuQeRkm5NMpJWZG3hSuFU= for SHA-256).

This behavior can also be exploited if a malicious user gains access to the SignatureValue of the empty string. Because the hash of the canonicalized SignedInfo is what produces the final SignatureValue, an attacker who possesses a precomputed signature for an empty string can reuse it to create a fully valid signature over an arbitrary SAML Response message.

Another exploit of the libxml2 canonicalization logic can be found in my previous exploit of the CVE-2025-25292 in the SAML Raider repo. Unfortunately, this is not well-formed XML, and can not be used any more.

The ruby-saml 1.12.4 and php-saml libraries are vulnerable to the canonicalization exploit, and other PHP XMLDSig implementations, such as Rob Richards’ xmlseclibs are also affected. In contrast, the XMLSec Library and Shibboleth xmlsectool are not vulnerable.

An example of such a "Golden SAML Response" (a message that always passes signature validation, regardless of how the assertion claims are modified) is available in the GitHub Samples folder.

Even if a malicious user cannot directly access a signed SAML Assertion, it does not mean there are no valid, IdP-signed XML documents available publicly. Several types of legitimate, signed data can be repurposed for exploitation.

The most straightforward source is SAML metadata. Unfortunately, these files are rarely signed, but in some cases, a signed version can be retrieved by appending parameters such as ?sign=true to metadata URLs.

Another reliable source is the signed error response. According to the SAML specification, the Request Abstract Type requires only three attributes: ID, Version, and IssueInstant. These form the minimal structure for a valid SAML request message. As defined in the SAML Core 2.0 Specification:

If a SAML responder deems a request to be invalid according to SAML syntax or processing rules,

then if it responds, it MUST return a SAML response message

This means that even when a request is malformed or syntactically invalid, the Identity Provider (IdP) may still issue a signed error response to indicate the failure. Invalid AuthnRequest showed below:

<samlp:AuthnRequest

ID="€"

IssueInstant="INVALID"

Version="INVALID">

</samlp:AuthnRequest>

A signed error message can also become a source of a void signature if the reflected error content inside the response triggers a canonicalization error, resulting in the digest being computed over an empty string.

Finally, Web Services Federation metadata is almost always publicly available for major identity providers. These documents provide a convenient and legitimate way for attackers to obtain valid signature elements, even when the XML is not fully compliant with the SAML schema.

Putting all together:

In this large SaaS real-world scenario, which cannot be disclosed in detail, we used the Ruby-SAML exploit together with Gareth Heyes’ research, "Splitting the Email Atom: Exploiting Parsers to Bypass Access Controls" to generate a forged SAML Response, create a new account, and ultimately bypass authentication.

You can download the Burp Suite extension that automates the entire exploitation process from GitHub. These vulnerabilities will also be added to the SAML Raider extension - stay tuned.

To mitigate the risks described in this research, the following best practices should be adopted when implementing or maintaining SAML authentication systems:

Reliable authentication security cannot depend on unsupported or poorly maintained libraries. Comprehensive and lasting remediation requires significant restructuring of existing SAML libraries. Such changes may introduce breaking compatibility issues or regressions, but they are essential to ensure the robustness of XML parsing, signature validation, and canonicalization logic. Without this foundational rework, SAML authentication will remain vulnerable to the same classes of attacks that have persisted for nearly two decades.